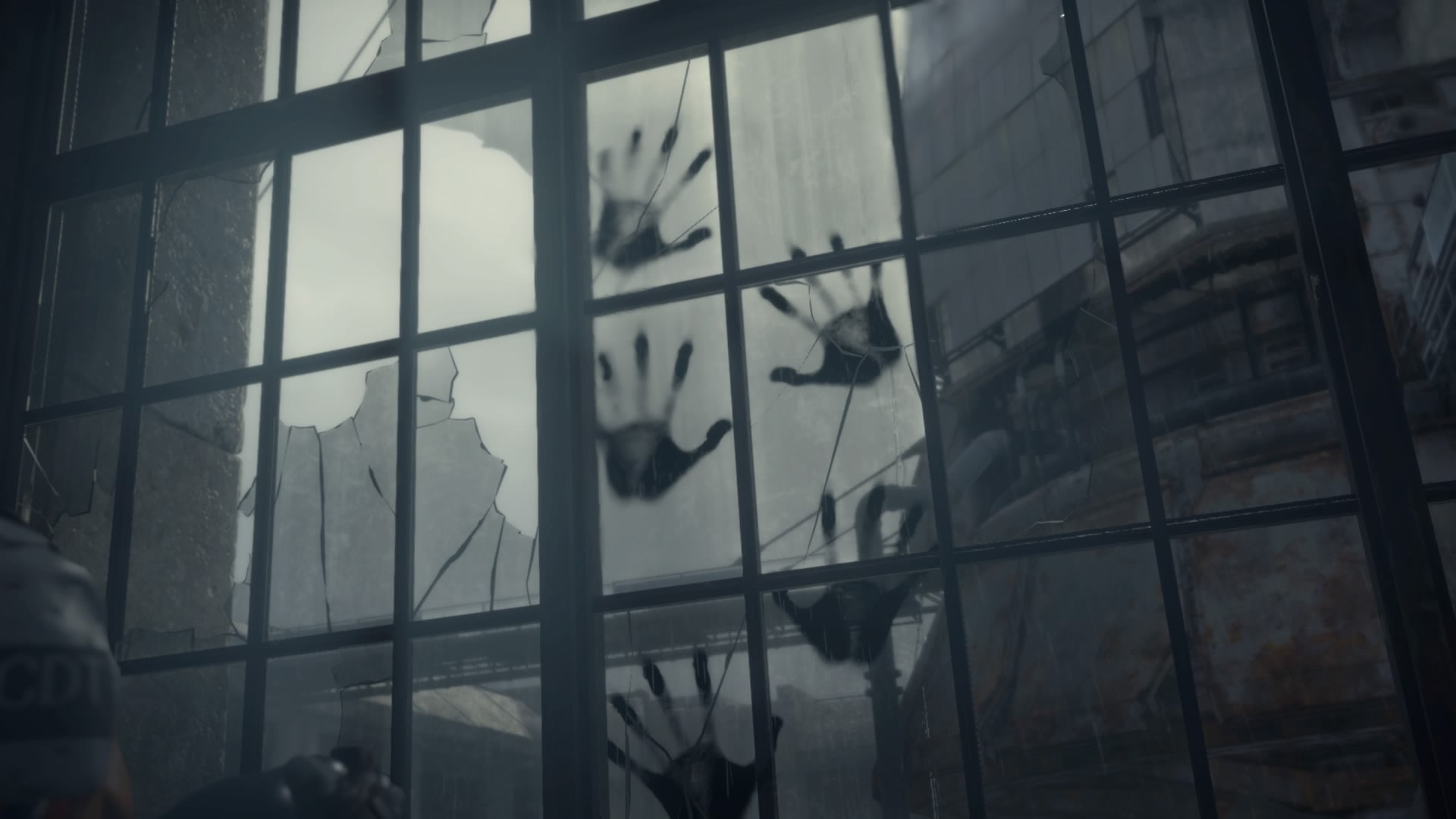

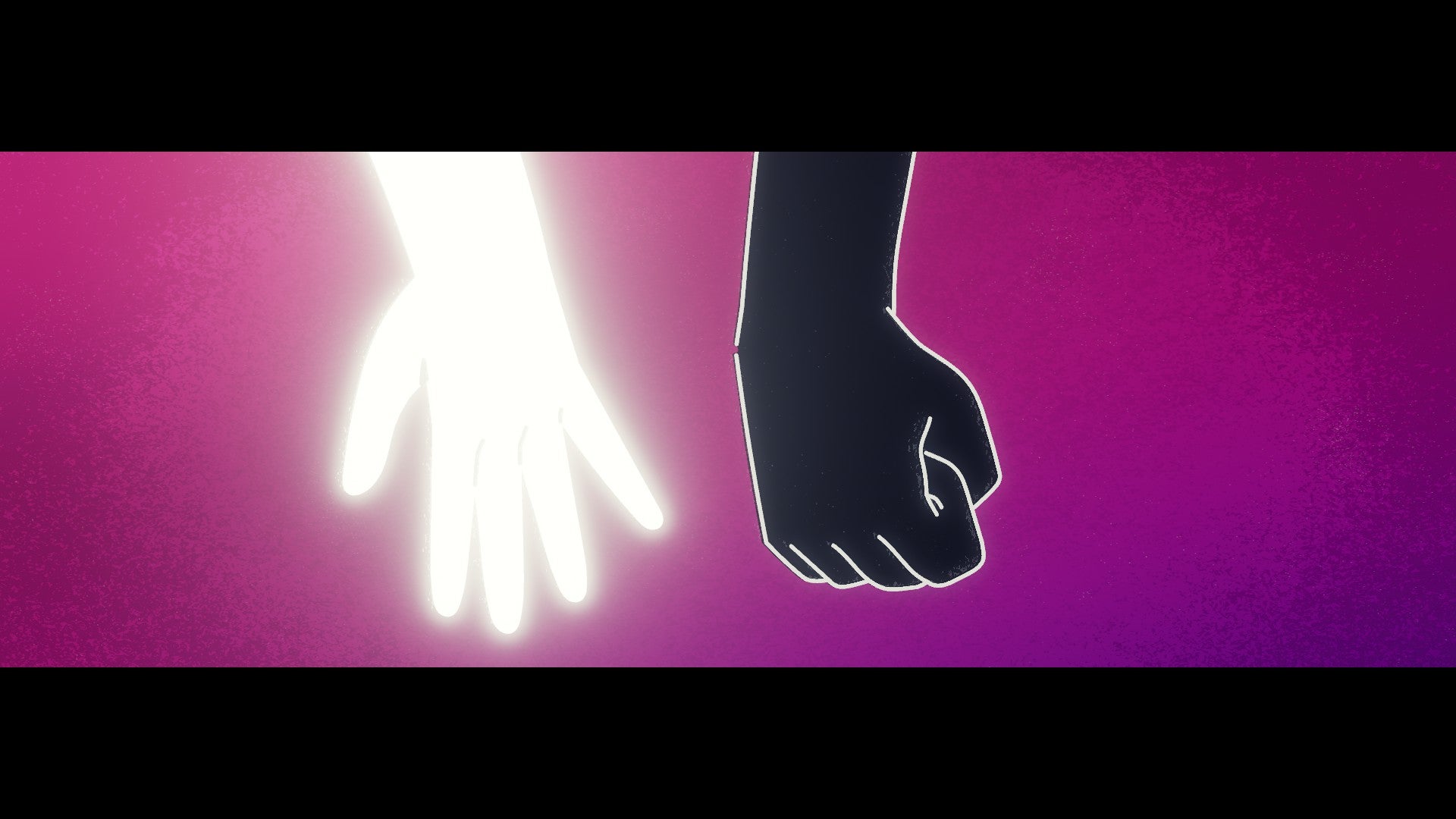

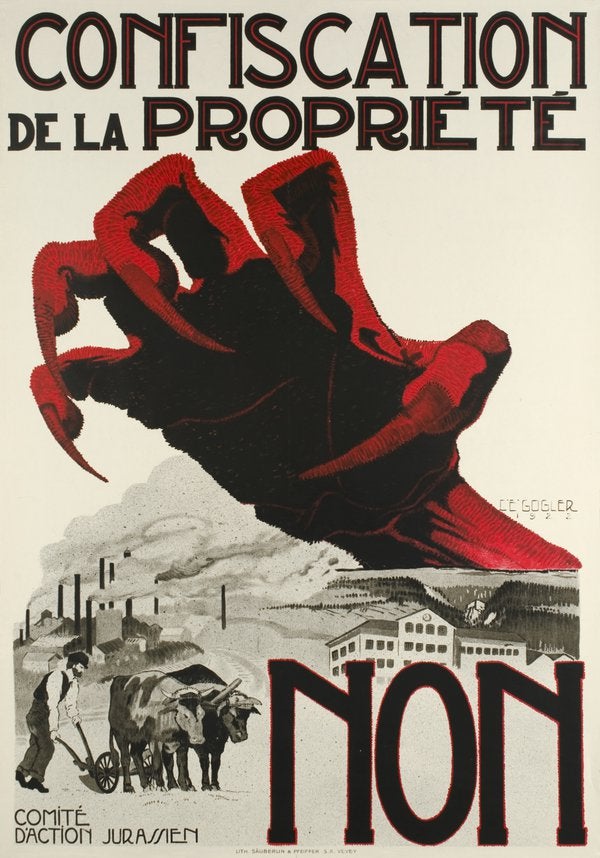

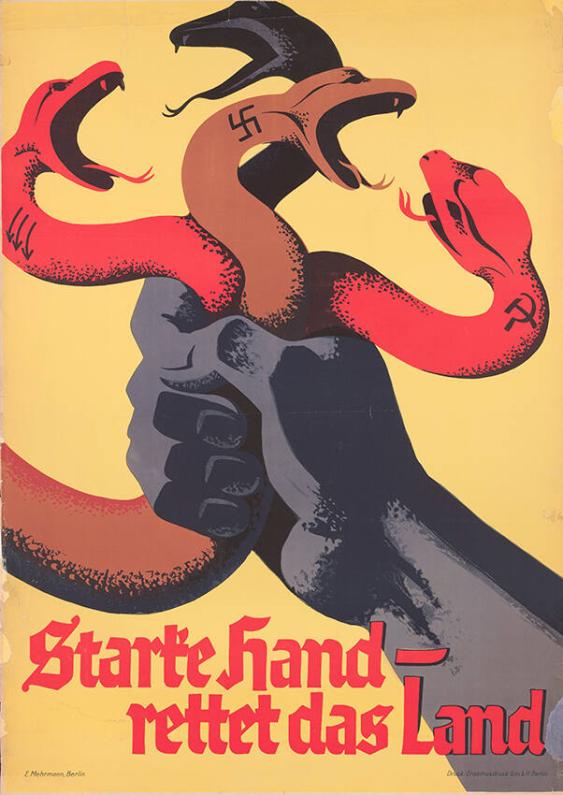

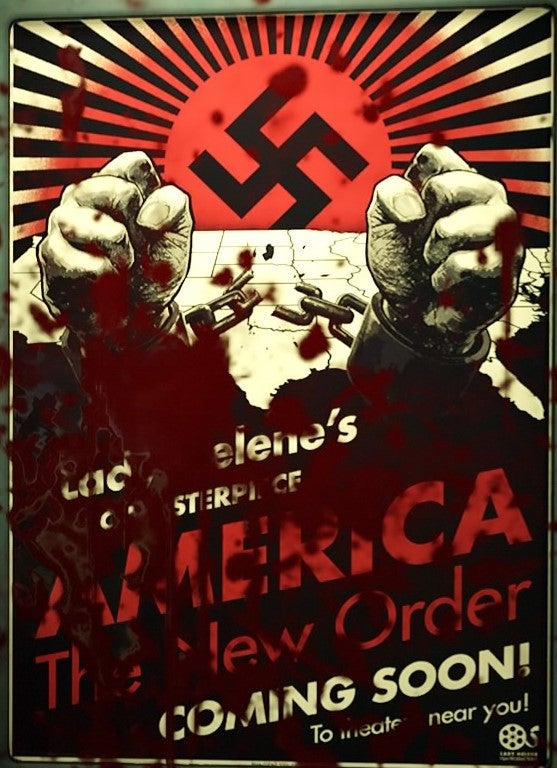

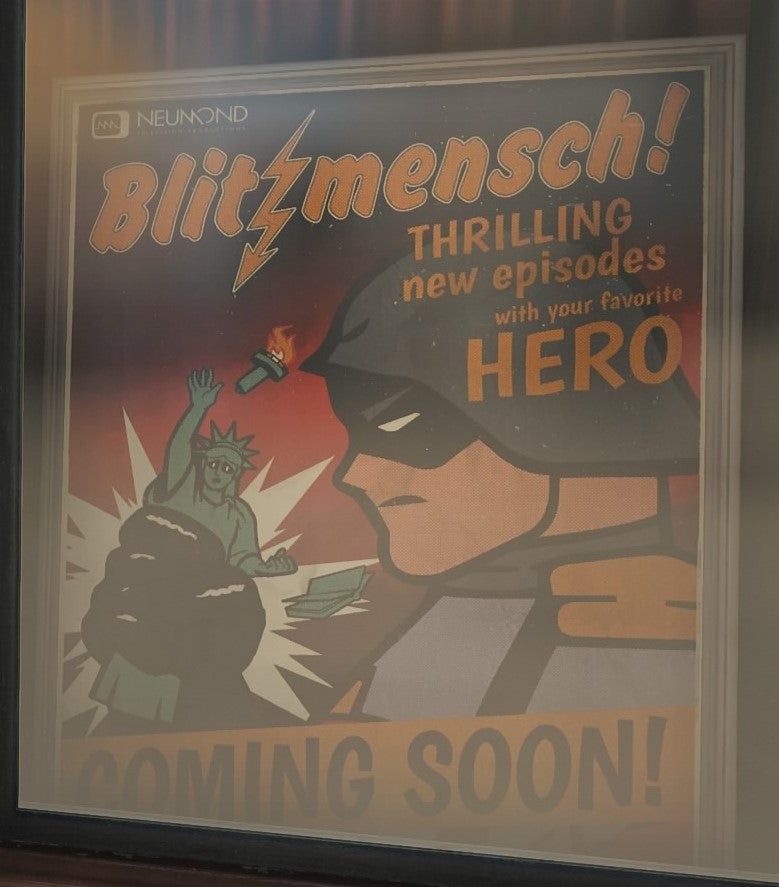

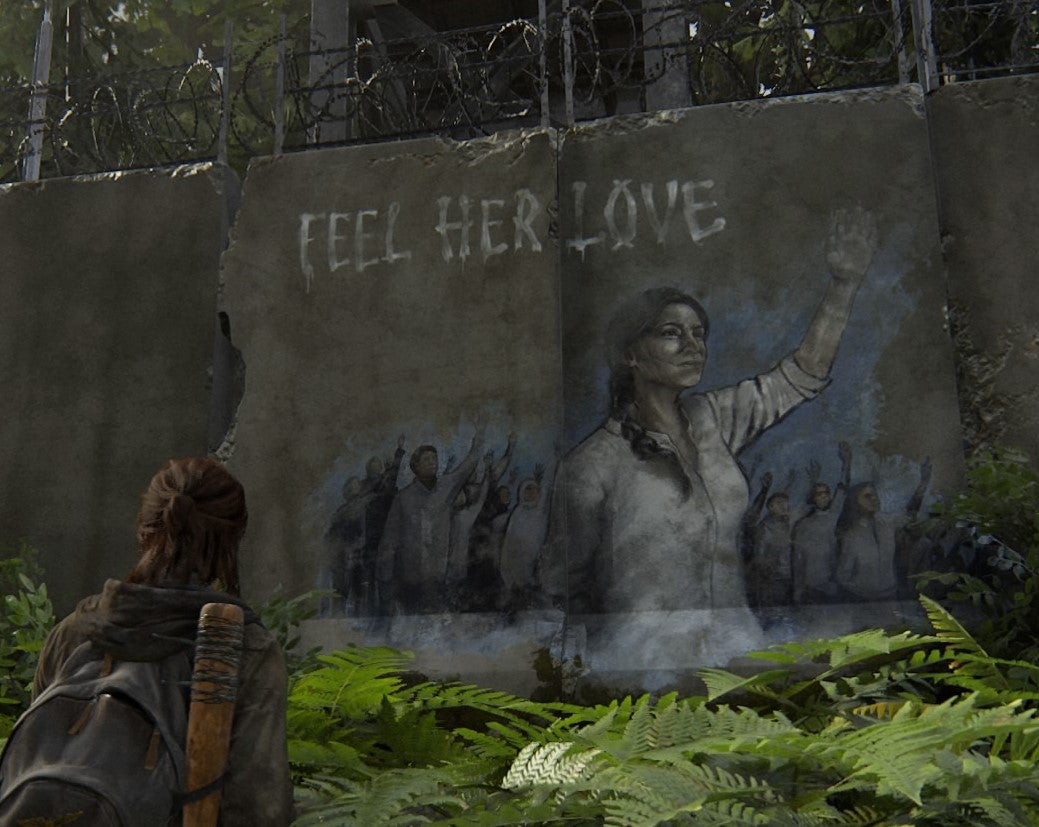

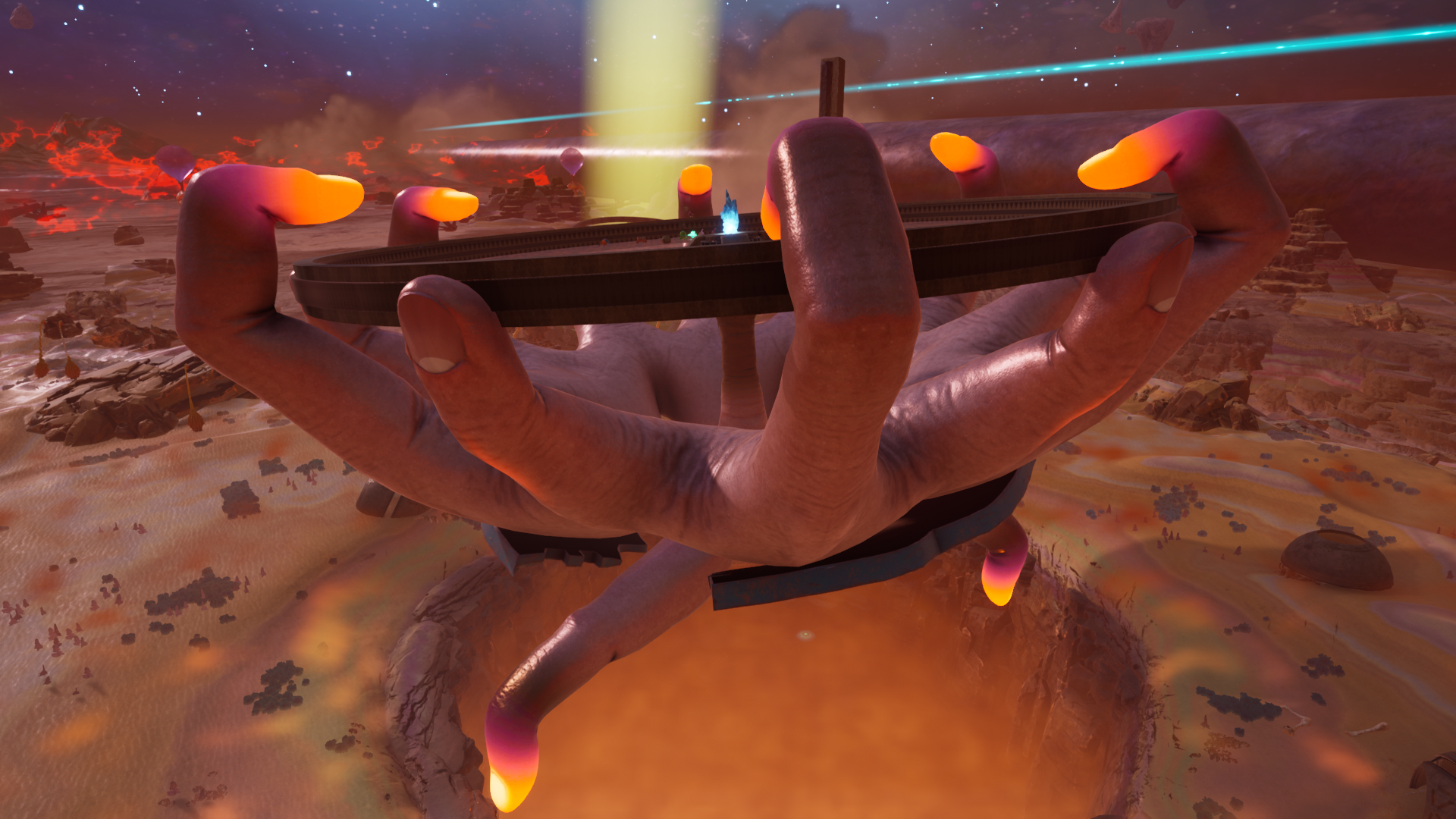

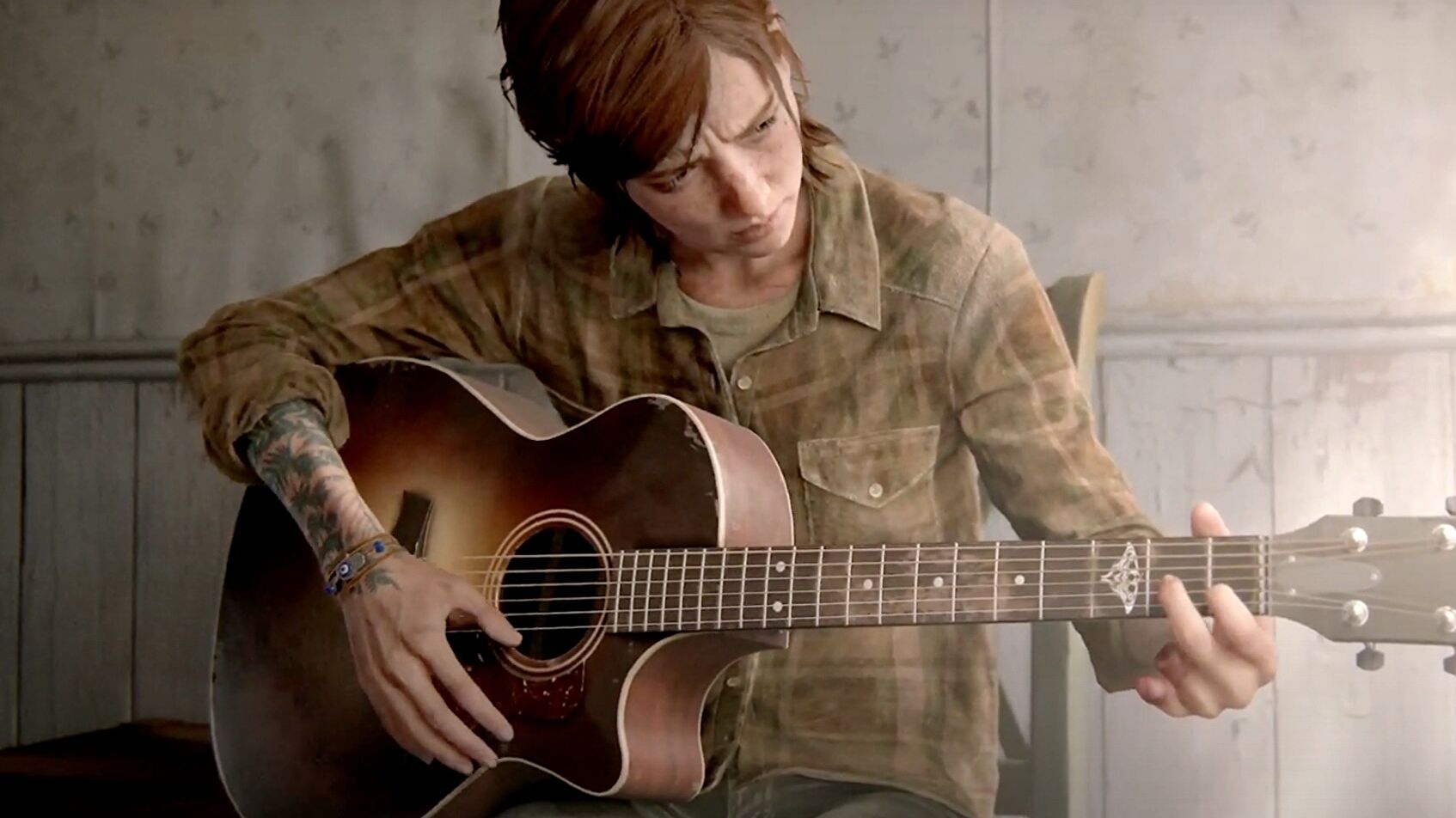

And yet, hands are far more than just tools to get a job done. Ever since its discovery, the Cueva de las Manos in Argentina has fascinated people with the stencilled handprints of hundreds of human beings. Some of them reach out to us over a historical distance of nearly 10,000 years. There’s something both mysterious and mundane, distant and intimate about this sight. We can’t know the minds of the humans that left their handprints behind, but we do know that they were people like us, exploring and connected to the world around them through their hands. The Cave of Hands made its way into several video games, Psychonauts 2 and Genesis Noir among them. They’re far from the only games to show appreciation for hands, and handprints in particular. Just think about how the bloody handprint on the wall has long become the tired cornerstone of environmental storytelling in countless horror and action games. Death Stranding takes this obsession with handprints several steps further, making them a central symbol of its narrative. Handprints on the ground or on walls are one way of recognising the threat of the game’s invisible ghost-like BTs. Even on the skin of our protagonist Sam, they’ve left their marks. They become a symbol for Sam’s fear and distrust of human connection, exemplified by his repeated refusal to shake hands with anyone. The inhabitants of the game’s post-apocalyptic world are haunted by the intimate absences of ghostly hands, in a literal as well as a figurative sense: the inherent potential of the hand to both hurt and comfort, push away and embrace, destroy and mend, communicate and silence. Death Stranding is not exactly subtle in its symbolism, but it does succeed in highlighting the powerful ambiguity of the hand’s significance, and our ambivalence towards it. Sometimes, this ambiguity is resolved beyond a doubt. The expressive power of the hand is great, and it can be used as an effective shorthand (excuse the pun) to convey a variety of messages or emotional states: hands folded in front of the face signal grief; a fist, aggression; a hand raised above the head stands for a call for help; a hand outstretched and turned upside down, a gesture of giving. Hands are so good at emotional expression, in fact, that the history of political propaganda and symbolism cannot be disentangled from the history of the hand within art. The political posters of the 20th century are full of fists smashing enemies and injustices or being raised in a gesture of strength and solidarity. We also find the transgressive and groping hands of a societal bogeyman threatening the nation, or helping hands offered to the downtrodden. Video games have made this visual language a part of their own. Just think of the satirical posters of Wolfenstein 2: The New Colossus, full of fists symbolising the strength of American fascism, the messianic graffiti of The Last of Us 2 with raised hands as a symbol of solidarity, or the Magister’s insignia in Divinity: Original Sin 2, consisting of a threateningly splayed hand with a single eye in its palm, evoking both surveillance and totalitarian control. It is exactly the intimate, innocuous familiarity of the hand which can turn it into a creeping and alien horror, each finger a leg or feeler fumbling towards its prey. Dark Souls 3, Elden Ring and The Eternal Cylinder all feature monstrous hands as distorted and disjointed threats. Remove the human agency from the hand, and what remains is something horrifying and uncanny. To understand why, one need only look back to the Cave of Hands and the feelings it inspires; the hand may be the most powerful symbol for our shared humanity. Take away the humanity, and it becomes an empty husk, threatening our identity as a species itself. Elden Ring’s Two Fingers encapsulate some of the ambiguity within hands. Their alien and off-putting appearance keeps us on our toes, but they are also expressive and benevolent guides; at least, that’s what we’re told by the Finger Reader Crones, who claim to be able to “interpret the words of the Fingers, envoys of the Greater Will.” The item description of the Two Fingers Heirloom tells us: “Fingers cannot speak, yet these were eloquent. Persistently did they wriggle, spelling out mysteries in the air.” The expressive power of the hand is still there, but it has exchanged its immediacy and clarity for secrets and mysteries beyond the human. This is the hand as other and potentially threatening. What happens if the hand is our own? On the one hand, their potential for violence becomes both a symbol and a tool for our agency within a digital world. The best example of this are first-person games; in games like Wolfenstein, Dishonored or Bioshock, the hands of our avatar on the screen bristle with potential and power, visualising both whatever killing tool we have equipped at any given time as well as our general readiness to inflict our will upon the virtual playground. On the other hand, destruction, no matter how prevalent, is only part of the story. Hands are maybe our most intimate and familiar feature of the self; no other part of ourselves is quite as omnipresent in our perception. Extended into, or rather doubled on the screen, hands can become a symbol not just of violence and domination, but also of selfhood, presence, and expression. It’s no coincidence that avatars are less embodiments of our bodies and rather of our hands. That’s doubly true for VR games with their focus on translating real-life movements into the game. Often, the hands are the only feature of our supposed virtual body we can see; disembodied hands floating in empty space. Every other part of the body would only get in the way. It is implied, and that is enough. A single hand on the screen acts as a metonymy, a stand-in, not just for the body, but also for the self. Some games seem to understand this better than others. Bioshock is almost as single-minded in its focus on hands as Death Stranding. For all intents and purposes, our main character is a pair of hands, and nothing more. Everything is expressed through them in a manner that’s as effective as it is unsubtle. Power, pain, cruelty, selflessness, agency or the lack thereof; all of it is conveyed through a hand with a chain tattoo on its wrist. The good ending shows our dying protagonist’s arm, its aged skin and faded tattoo, lying on a hospital bed, surrounded by the little sisters he’s saved. We only see what’s necessary: their hands. In The Last of Us Part 2, there are several sequences where Ellie takes her guitar and the game asks us to play for her, controlling the movement of her hands. During her quest to avenge Joel’s death, Ellie loses two fingers on her left hand. When the game asks us to play the guitar for a last time at the end of the game, we realise that the missing fingers make it impossible for us to do so. Having sacrificed a part of her in the name of Joel, she has lost her last means of feeling close to him: playing the guitar. A more extreme example is Brothers – A Tale of two Sons, in which we control two brothers simultaneously. The left half of the controller is responsible for one character, the right half for the other. After one of the brothers dies towards the end of the game, half of the controller – and thus one of our hands – loses its functionality. Again, the hand becomes a metonymy of the self: the loss of our hand’s purpose is equated with the death of the brother. Once we bother to look, we find handprints all over our games. We shouldn’t be surprised: hands are powerful. They suggest and express. They empower and victimise. They stand for violence as well as vulnerability, for shared humanity as well as monstrosity, for self as well as the loss of self. We may manipulate games with our hands, but sometimes, the hands within the game manipulate us right back.