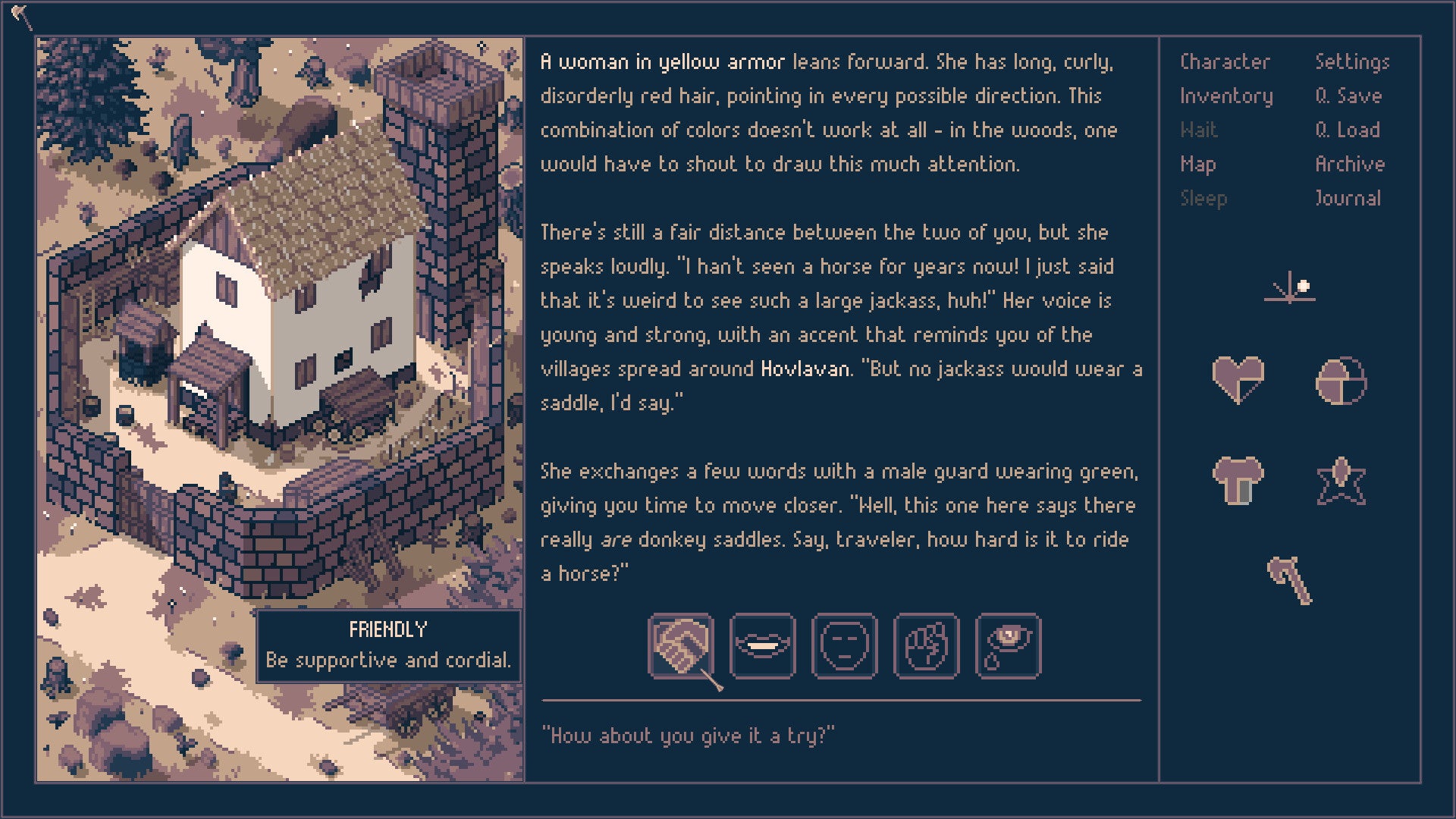

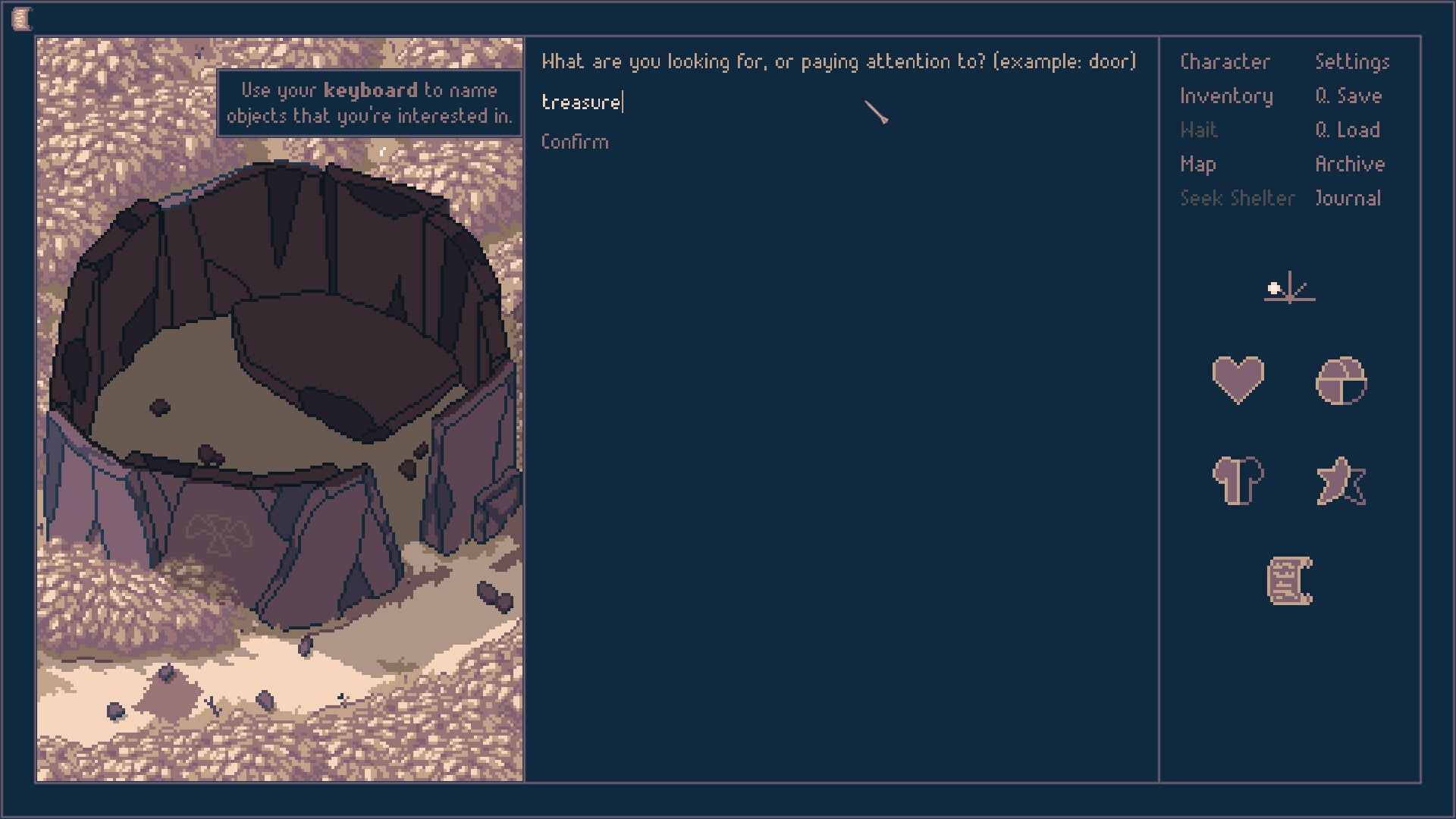

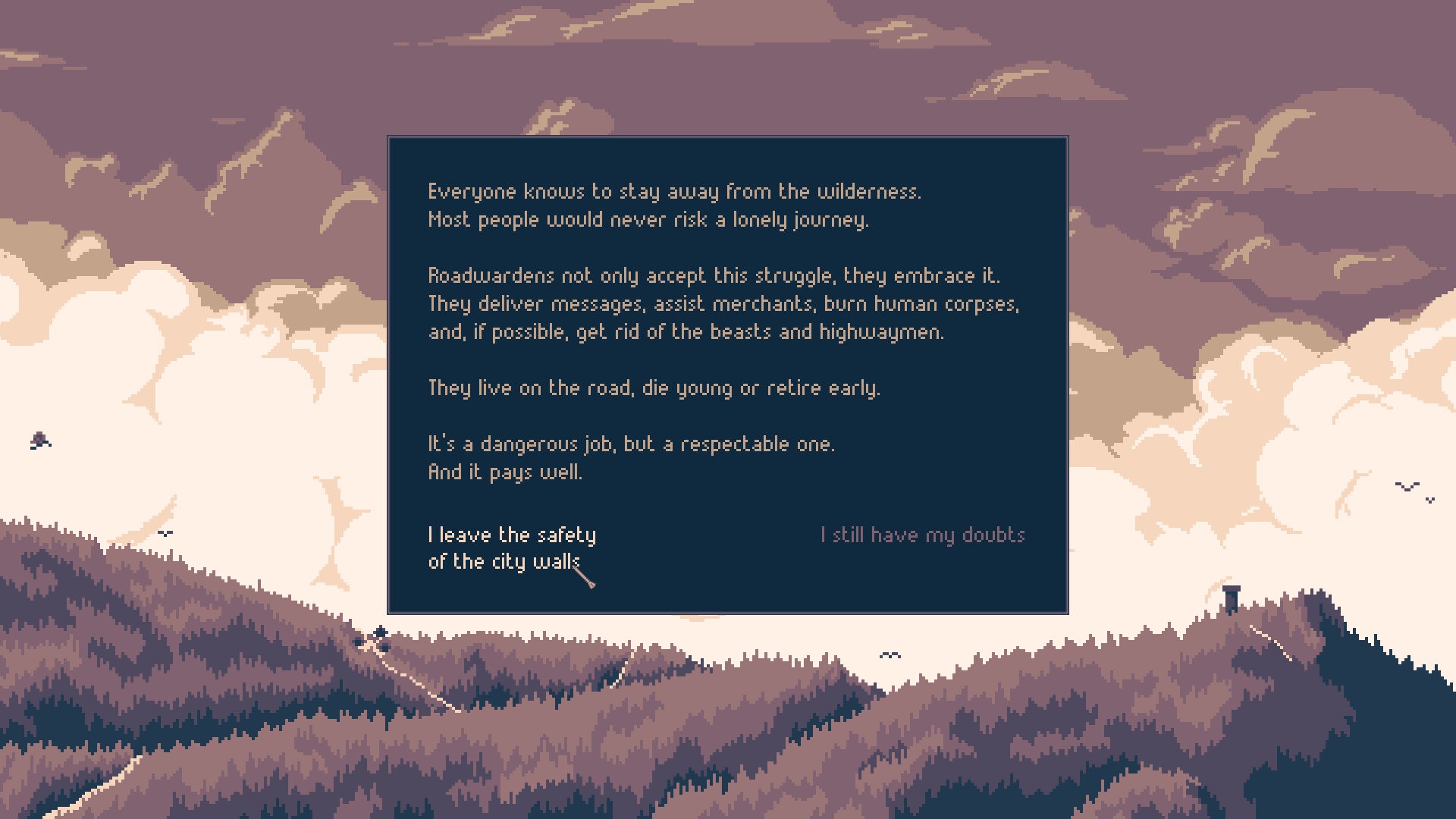

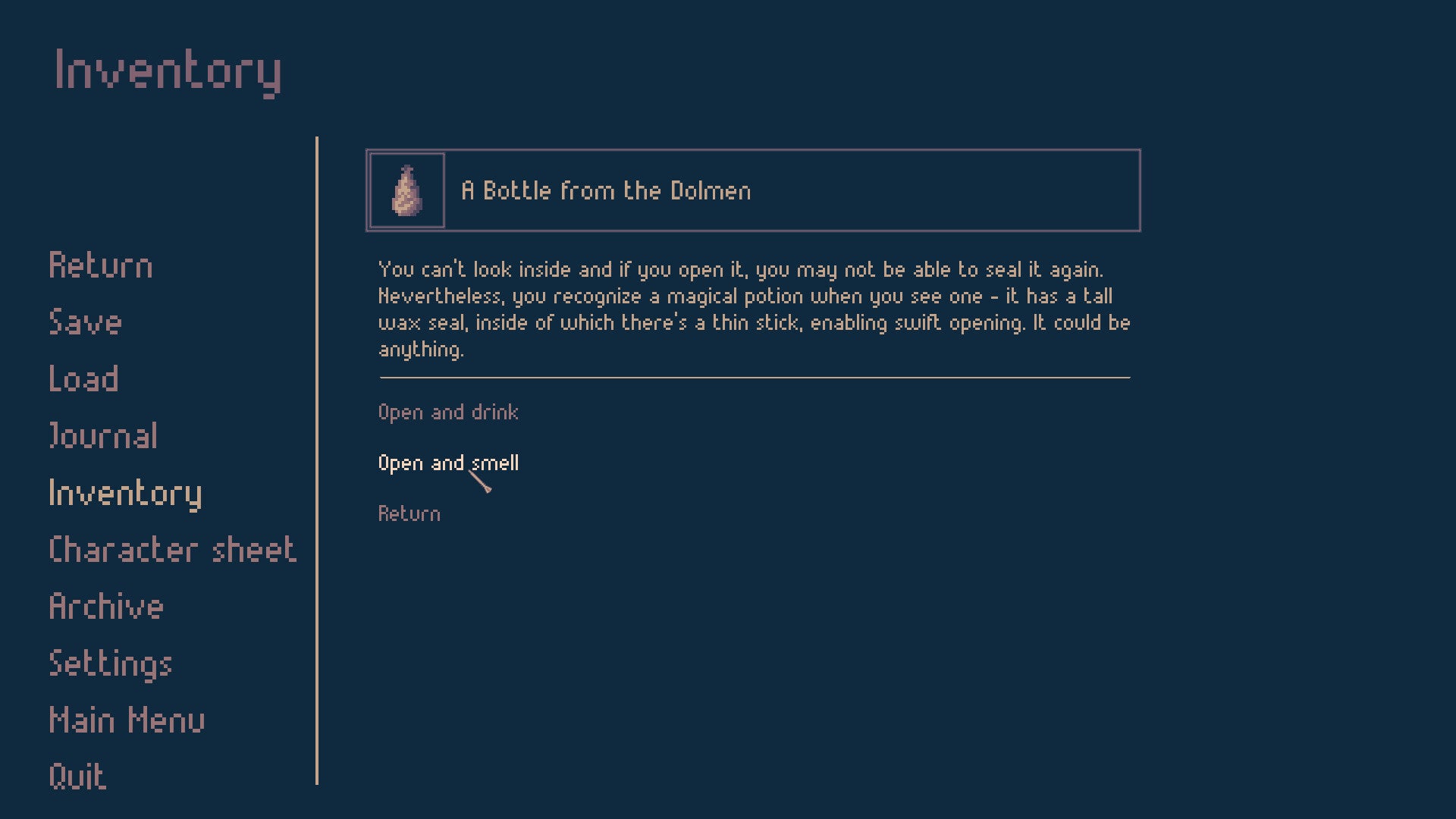

I admit, when I started the game I felt a little contemptuous of him. Roadwarden’s setting is hardly gigantic – dredged map node by node from the fog of war, it consists of a single road looping a dense, watchful wilderness – and many of the problems you encounter seem trifling. A monk awaits a package of fine quills. A couple of foragers need help lassoing and subduing a massive, flightless bird. A carpenter wants you to shore up a ford. This isn’t Dragon Age or Skyrim, but a deceptively sleepy choose-your-own adventure with deceptively delicate RPG appendages, its locations consisting of terse yet evocative descriptions and nested dialogue choices, beautiful eight-colour isometric dioramas and a soundtrack of animal sounds and melancholy guitar. There are no armies to slay and no ability trees to scale, though you might pick up a new axe and a fancier padded jacket on your voyages. Your first few conversations with soldiers and innkeepers suggest a society of needy bystanders to be systematically won over by fetching herbs and rescuing lost puppies. How hard can it be, I thought. But the more I played, the more setbacks I encountered, and the more I came to identify with my missing predecessor. The peninsula is at once decaying and divided, awash with bad blood, questionable sorcery, religious differences and automatic mistrust sharpened by penury: to aid one village may be to incur the wrath of another. Nobody particularly wants you around, to begin with - and that’s assuming you’re here to help rather than lie, steal, intimidate and in general, drive everybody deeper into the muck. Just staying in one piece is a feat: the woods crawl with griffons, bloodthirsty apes and giant spiders, so each evening you must find safe and, preferably, comfortable sleeping quarters, or take damage while journeying after dark. Often, the best you can afford is a tavern bench or a pile of furs in a shack, which may leave you drained and dishevelled in the morning. You have to worry about your health or “vitality” and strength or “nourishment”, but also, hygiene and tailoring: wander into town decked in rags and filth, and you may have trouble persuading locals to give you jobs or share knowledge about the wider world. Above all, you have to worry about the passage of time, which advances whenever you travel or undertake a task. The merchant guild wants you to report back in 40 in-game days or less, beginning in late summer and ending with the onset of autumn. There’s the option to play with this restriction removed, but I think this misses something essential about Roadwarden, while also decreasing the incentive to replay and test out different starting vocations, dialogue choices and priorities on your to-do list. I finished my initial time-limited tour with around half my quest log complete, and was treated to a gruelling epilogue in which the consequences of my failures swiftly came to bury my - I thought, notable - successes: communities picked apart by imperial capital, then overrun by dark magic, half the settlements devastated, their secrets left to fester. I had given my character the personal objective of building a new home on the peninsula, but she ultimately met her death as a mercenary many leagues away, unloved and forgotten. Like Asterion, I left behind a trail of fleeting victories and lingering disappointment. But I also felt the meaningfulness of what I did achieve all the more. So much of Roadwarden’s power derives from its sense of entropy, which bleeds into everything from its many, meticulous descriptions of rot and wreckage to the decreasing number of daylight hours as the season advances. Choices matter, here, simply because you can only make so many. A dismal end… to an enthralling 20 hours of roaming, learning, befriending, investigation, deduction, risk, wonder, terror and sorrow. Roadwarden is, all told, one of the most absorbing, considered and rewarding fantasy games I’ve ever played - not quite as breath-taking as Planescape or Disco, perhaps, but a tale told with skill and heart and flair. That’s in large degree thanks to the understated role it gives you as player - a glorified odd-jobber and roadside handyman, similar to Geralt in The Witcher 3, but without Geralt’s superhuman fighting abilities (and certainly without his way of with the ladies - you’ll spend more time arranging marriages than bedding people, though I did manage to have one casual fling). Even if you choose a warrior background, adding points to the game’s hidden dice rolls during physical challenges as long as you have enough vitality, you’ll rely on your wits and insight far more than your axe blade. I played a middling mage with a pocketful of charms that allowed me to Force Push packs of predators, either to injure or scare. But I cast spells more often to restore myself while sleeping in rough conditions, or sniff out enchanted objects and curses. Play as a scholar, meanwhile, and you’ll be able to brew up exotic potions, but I’m more intrigued by the idea of being able to read and speak ancient languages, like the carvings I discovered in a dolmen during my initial run and never got round to deciphering. Rather than being separated off as capital-A Abilities, as in most RPGs, your class skills are threaded into the game’s narrative and dialogue writing, offered to you where they agree with the situation. They are believable, practical aspects of a setting that brings each esoteric flourish back to everyday questions of survival or human relationships, and which builds many challenges around remembering what you’ve learned or heard elsewhere and making a deduction - thankfully, there’s a conversation archive and a well-structured lore codex for easy reference. While universally hard-up, the people you meet cover a wide range. Outwardly sunny, inwardly calculating mayors; sinister men asking for directions in the deep forest; pesky children; jovial hunters; a hermit enchantress with a golem entourage - all have agendas, secrets and opinions they may deign to part with should you do them enough favours, or increase your standing with their friends. Some will offer their services as companions - part of a lategame scenario I wasn’t able to reach during my playthrough. Others will tell staggering lies that only reveal themselves once the damage is done. You’ll meet with grief and malice all over, but also, captivating accounts of the wilderness and moments of winning eccentricity. This is a society in which horses are more exotic than giant saurians, where some mages guard peat for a living, and you can learn the fine art of smoking and storing fish while asking about the local undead problem. It’s also a relatively tolerant setting, for all its troll-eats-troll politicking. There’s no discrimination based on gender or sex, nor do you encounter racism, though the world’s history includes slavery. Divisions tend to be economic or religious, with each faith strongly defined by its attitude towards nature and the nonhuman. Roadwarden presents the latter as a unified cosmic opposition, with creatures mounting mass invasions if humans encroach on the wilds too greedily. As the roadwarden, shoring up paths and restoring old camps and watchtowers, you risk kindling this apocalypse - hence the outright hostility of earthier factions, like the druids. I didn’t encounter any vengeful animal migrations during my playthrough, but there’s an ominous stat for creature deaths that makes me think of the closing scenes from Princess Mononoke. The intricacy and imagination of the writing is reflected in the diversity of choices you can make in any given scenario, which, again, typically rely on your local knowledge. Here’s a highly non-exhaustive list of questions I’ve wrestled with: what colour should I choose when using magic to illuminate a cave? Is it worth buying a shield I don’t really know how to wield? When gambling with the village youth, do I flirt or focus on the dice? Should I sit next to or across from somebody I’ve just met? Who do I trust to faithfully translate a wax tablet? Can I work out where a fellow traveller calls home from their accent? A few puzzles see you typing in words yourself - deciding what to focus on when confronted by a giant spider, or who to ask for in a village where nobody volunteers any information upfront. Elsewhere, you’ll peel back perilous locations section by section, braving the shadows of a mine shaft or fending off inexplicable nausea as you circle a ruined hamlet. You’ll also do plenty of wheeling and dealing. Roadwarden is one of the few fantasy games I’ve played in which the exchange of goods and wealth forms a compelling articulation of the world. It couldn’t be further from the abstract, homogenising way most RPGs think about money and resources - either mined from the simulation in passing or worse, at the expense of your enjoyment of places and their stories. Each village is defined by the specificity of its trades and economic relations as much as, say, a plague outbreak or the Chosen One ambitions of a local necromancer. There’s a common currency, made of shaved dragon bone, but some people are more interested in gossip, spider silk, or a helping hand. Fish - harvested from traps you can set along your circular route - can be bartered for rations or bones or safe passage, depending on who you’re talking to. The goods themselves are often belongings with the suggestion of a vivid history, which makes it hard to sell them even when your stomach is empty. One community requires that you work for your lodgings; another lets you sleep on the floor for free, as long as you clean up after your horse in the morning. Time is a factor in resource production: you can’t just buy infinite rations from a tavern keeper even if you do amass the means. Aside from keeping your heart in your mouth, the value of the game’s lightweight survival systems is that they encourage you to grapple with all this. While it can feel early on as though you’re trapped in a spiralling economic endgame, lacking the spending power to make headway, the feeling is misleading. Starving yourself or running out of vitality isn’t an automatic game-over: it just raises the odds of meeting your death in an encounter. And as long as you keep warding the roads, looping the forest, you will find work, refuge, foraging spots, the odd treasure - all of it feeding back into the game’s web of stories. A major consideration is when to brave the peninsula’s single shortcut, a neglected path right through the heart of the wild where you’ll face the most terrible creatures. There are quests to pursue here, but also, efficiencies; the forest road lets you shave away travelling time as the days grow shorter, and the weather less forgiving. One of Roadwarden’s best qualities among heroic fantasy RPGs is that it never forgets that you’re an invader. Assuming you don’t enthusiastically embrace your status as a spy for the guild, the act of discovery is always shot through with guilt. Every splendid detail of a place or person is something you’ll pass onto your paymasters, so that they can more efficiently rinse the region of wealth. Roadwarden doesn’t let you quit the guild at whim - when my time was up, I was automatically returned to the city. But it does leave opportunities to gradually set yourself on a different path. In particular, it effects a neat turnaround whereby you construct the imperial culture you represent in the course of describing your home city to the locals. How has the metropolis fared following that recent, devastating war? Is that infamously unsafe backstreet still a den of villainy, or has it been gentrified? Are the people still rather puritan, or has the need to share bathing space during sieges led to a sexual renaissance? In surveying this world’s perimeter, you also perform an accounting of the centre - a chance to imagine your own society in response to the game, to woo listeners with talk of a postwar urban utopia, or indulge your own cynicism. I can’t be sure, but I suspect that the epilogue you get is shaped by how cruel or accepting, greedy or kindly you make the city of your employers during these discussions. It’s one of many questions I hope to answer in my second run. This time, of course, I won’t just be following in Asterion’s footsteps. I’ll be treading in my own.