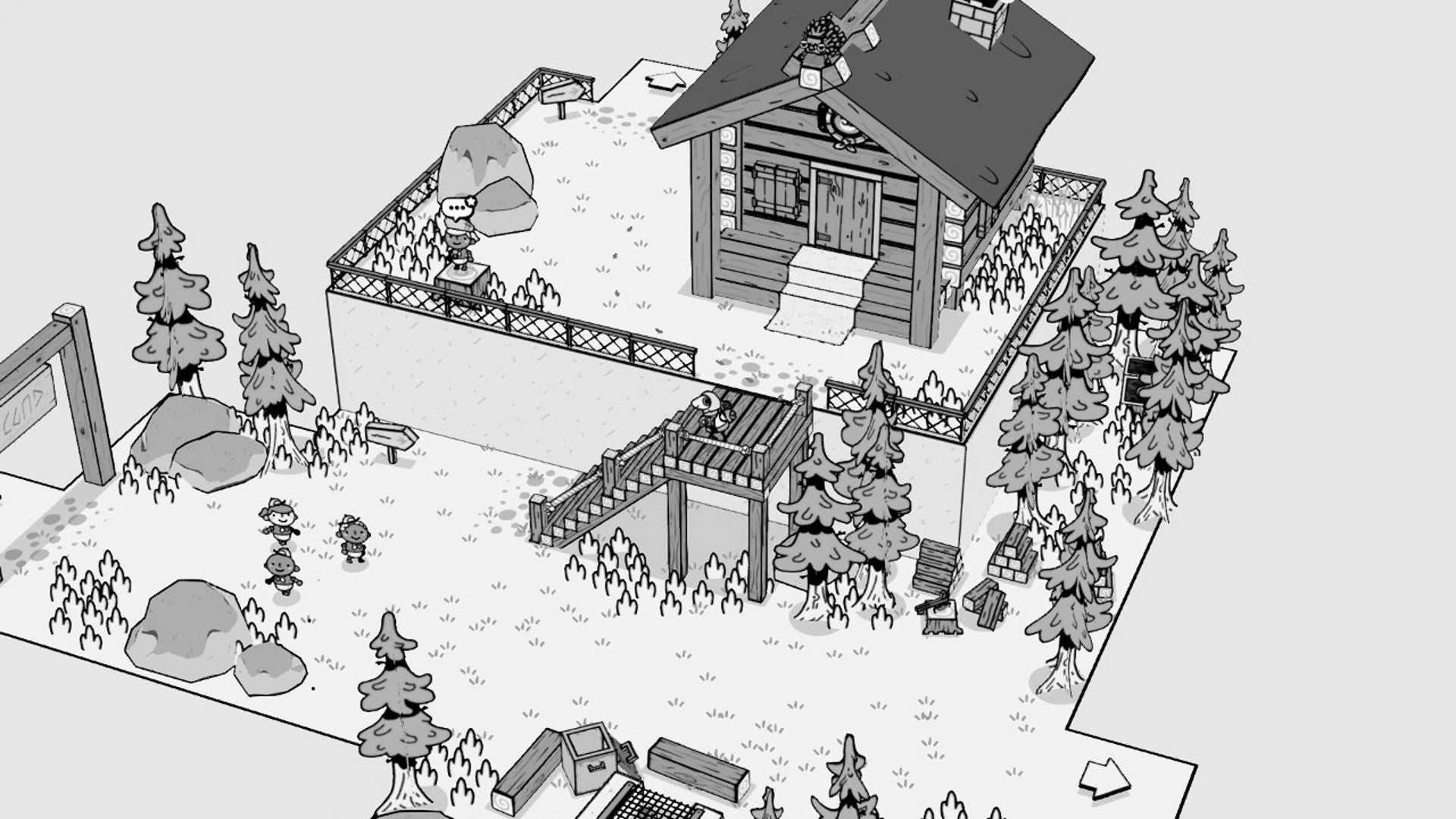

TOEM is one of the most charming and recent examples in this space, a game about exploring and taking pictures as you move through pocket-sized communities. But TOEM didn’t start as a photo game. It began simply as a non-violent game that would allow the player to stop and appreciate the game’s illustrative art style. The original idea spawned from a conversation two friends had about leaving game development forever. TOEM might not be their Final Fantasy, but the heart-to-heart sparked the sketch that would become the basis for the game’s striking art style. The road ahead would be long.

“We scrapped the game five times before coming up with the photographing version,” says Niklas Mikkelson, one half of the two man team at SomethingWeMade. “Lucas [Gullbo] remembered a telescope idea he tested out and told me, maybe we can do a camera.”

With just a camera, a tripod, and a photo album at the player’s disposal, TOEM does a lot with a limited toolset. On the other end of the spectrum of complexity, we have Umurangi Generation, a game that is both a masterclass in environmental storytelling and a low-key photo tutorial. Throughout the game, the player is unlocking new lenses and editing tools at a pace that won’t overwhelm newcomers.

Naphtali Faulkner (who works under the handle Veselekov) wanted to make a game where editing was just as important as the picture taking.

“The fun of the act of photography is picking the right lens and the right edits.” Veselekov says, detailing the game’s two core design pillars. “There is a lot of depth to picking a lens. When you start to get into photography, [you realise] lenses can see beyond the human eye. That’s a really important feeling to capture in photography games.”

Two of the main inspirations for Umurangi’s level design were the Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater series and Jet Set Radio.

“[In Tony Hawk] you stop paying attention to the scoring and you are just doing what you enjoy, so I was a little inspired by making this recreational activity into a game without losing the recreational aspect of it,” Veselkov says. “They had the right model there - you have the freedom to do the mechanics but you have objectives to take you around the map. With Umurangi the photo bounties are spread out but we put them in places we want people to see.”

One example comes in the Macro DLC level, Gamer’s Palace. The level is a dystopian bar and arcade, with tunes pumped in by DJ Tariq. The game doesn’t outright tell you who and what Tariq is, but one of the level’s objectives is to snap a photo of the DJ. The objectives can be tackled in any order and - if you aren’t going for the bonuses - in any amount of time. Ultimately, players are going to see what Ves wants them to see, but like he says, “It’s like when you hype up a movie to your friends and then they’re like ‘well it wasn’t that good.’” You have to let people discover the excitement, and the meaning, for themselves.

The Jet Set Radio influence is even more apparent to players who fully explored the Macro levels and unlocked the roller skates (an upgrade essential to speedrunners). But beyond that sense of speed and momentum, the setting and world of Umurangi Generation was heavily inspired by the Dreamcast series.

“Jet Set Radio is an inherently political game about resisting the state and [Umurangi is] taking these mechanics and bringing them to the 21st century,” explains Veselkov. “There are moments in Jet Set Radio where the police escalate in their aggression and it was played for comedy at the time. If it were to come out now we would respond differently.”

Umurangi Generation uses its photography mechanics to tell a story of resisting the state in an era where resistance in any meaningful sense is harrowing. It teaches the importance of photography in an age of conflict. In the meantime, the team at SomethingWeMade were using photography mechanics to emulate their favorite parts of the outside world instead of the most depressing ones.

“We wanted our mothers to be able to play it”, Mikkelsen says through a laugh. “We thought of ourselves when we were traveling. I always save all my photos from all my trips. It’s a magical feeling to look back a year later.”

This feeling inspired the game’s photo album, that players can open up and flip through at any time. If Umurangi focuses on teaching players basic photo editing, TOEM emphasizes the power of photos as personal artifacts. For the developers, this meant not overcomplicating the mechanics. “It fit the game to strip away complicated photo features. We often circled back to [the question] ‘does this add anything?’ Most of the time the answer was no.”

This was the design philosophy behind the Swedish team’s debut game. Every mechanic was subject to a thorough back-and-forth between the two-man team, to the extent that one of the game’s best elements almost didn’t make it in the final version.

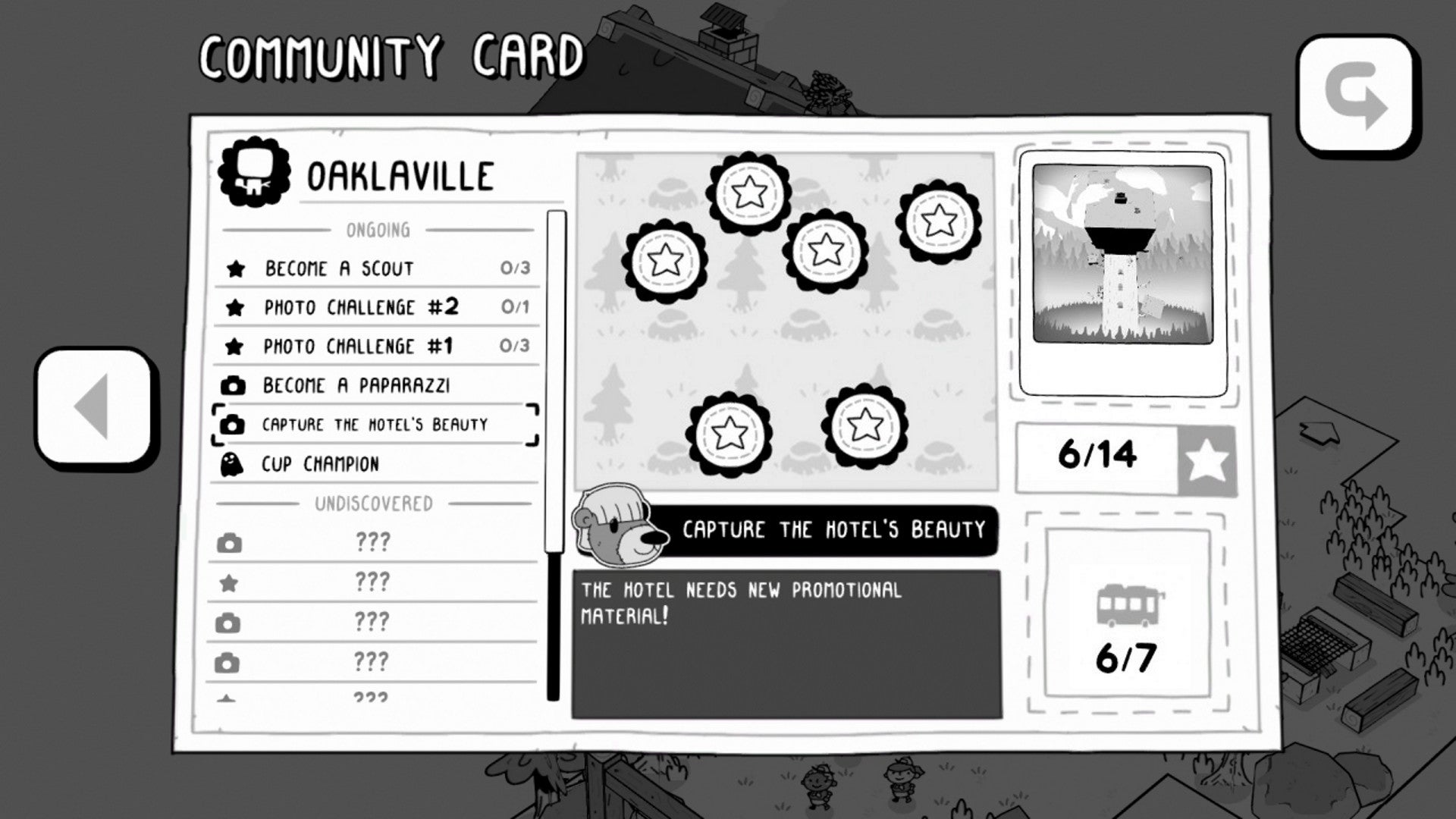

When you complete an objective in TOEM, the notebook opens up, the objective checks itself off, and then you get to add a stamp to your collection. The stamping in TOEM is one of the most satisfying mechanics of the year. This is all thanks to the game’s artist and other creator Lucas Gullbo.

“I think it’s more about just the stamp and about the whole complete quest cycle,” Gullbo says. “As the stamp hits the card the whole card wobbles a bit to indicate impact. As the stamp disappears there is a small pause in feedback and then jingle starts playing together with a little pop particle over the new stamp.”

The appreciation fans can have for these tiny details, the way the creator’s eyes light-up when you mention it is also your favourite part of the game - that’s the heart of why these games are getting made. To put the audience in a headspace of observing the world around them, in-game and otherwise.

From the developers’ standpoint, the appreciation for the art and detail the creators put into the world is a part of the appeal of photography games. The genre is about showing players around the world you built in a way that lets them be creative and, notably, non-violent. Umurangi Generation and TOEM illustrate the power of photography, whether it be as political protest or a conduit for reliving your favorite memories. This depth of emotion appeals to a generation of gamers who grow weary of the same violent actions we are asked to perform ad nauseum.

“It feels like a nice way to explore a world,” Gullbo says, “it focuses more on looking at things rather than destroying them.”

Ultimately, that’s the nature of photography. To preserve, not to destroy.