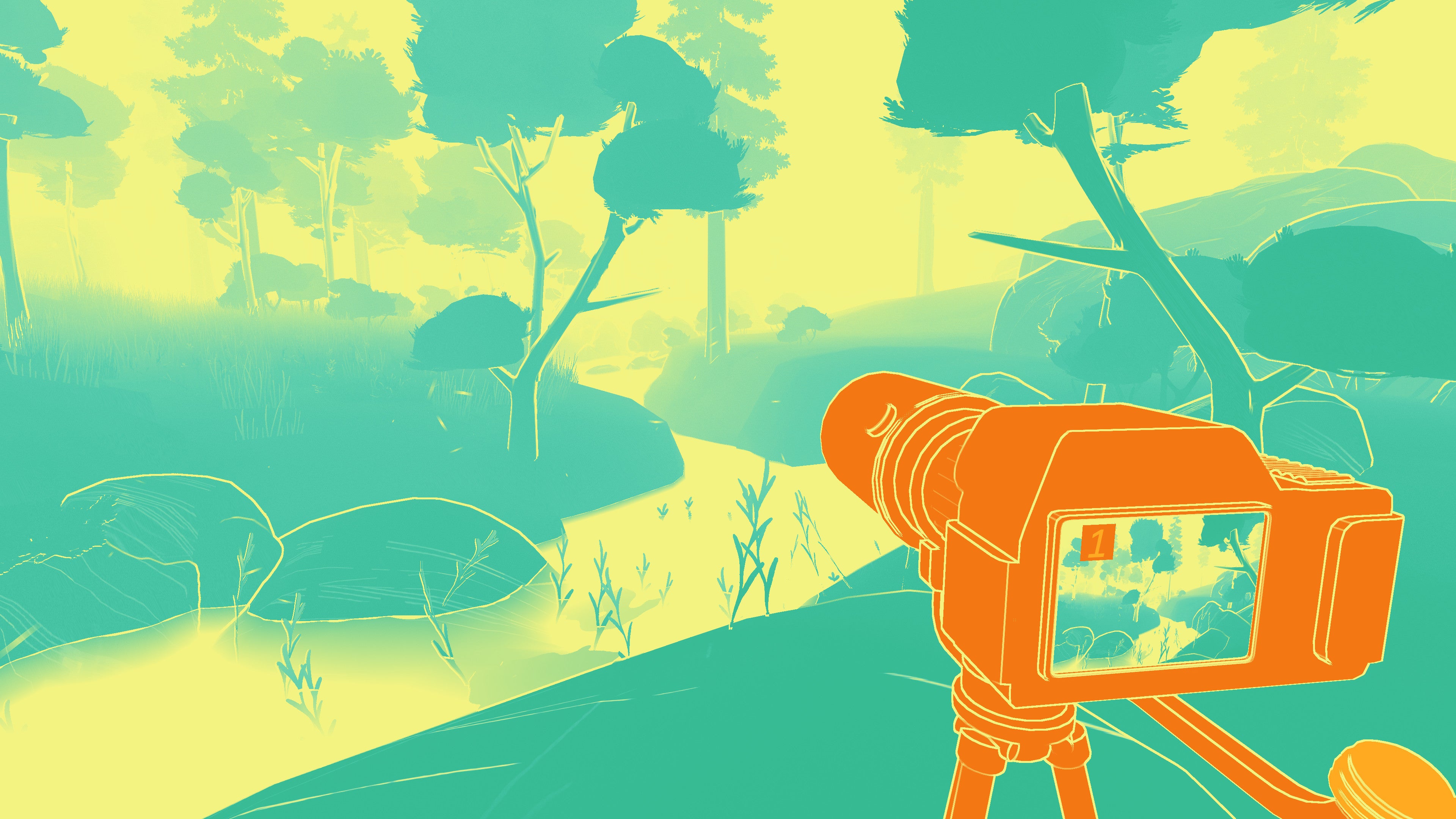

The line is always accompanied by a footnote admitting that, yes, Melville was clearly wrong about this one. We love penguins. Take a poll. Penguins are universally lauded. The thing they do with the rock. The eyebrows on some of them. The strong chocolate bar synergy for UK fans. We don’t even feel tricked when their awkwardness on land gives way to muscular elegance in the water. The awkwardness flashing into elegance at the moment of impact actually seems to suggest contiguous virtues. There are no penguins in Nuts - or if there are, I missed them. But I thought about Melville’s take on penguins because Nuts is all about squirrels - and squirrels, I suddenly started to realise, are not universally lauded. It seems at times that we can’t decide about them. They are cute and sprightly and move in a lovely fountain-pen ripple, sure, but up close there are those surprising sharp teeth, and so many of them! There are those glossy, inscrutable eyes. And then someone will say, “Oh, you know the grey squirrels killed all the red ones,” and then, maybe a little involuntary shudder? Maybe not. I think the wayward genius of Nuts is that it harnesses this ambiguity about squirrels - it harnesses the uncertain territory they occupy in our consciousness. The game’s central questions are basically: do you trust squirrels or do you distrust them? When you insinuate yourself into the squirrels’ world, what exactly do you find? How do you feel, instinctively, about a gathering of squirrels? These are questions the game answers, but that is beside the point. What matters is how this uncertainty fuels this unusual adventure and helps make it memorable. In Nuts, you’re a recent graduate student researching squirrels in Meloth Forest. You live in a camper van and spend your days placing cameras in the woods and your nights monitoring the feeds from these cameras. You communicate with your superior over fax and telephone, and although there’s something heavy in the air, the game’s first half is marked by a lazy bucolic sweetness. I finished Nuts a few days ago and I still want to go back, to the cosy camper with its domestic disarray, to the forest and streams and sky, delivered, like everything else in this game, as spectral outlines of the natural world stained the warm shifting colours of a Miami cocktail - hot pinks, dusk blue, reefy yellows and oranges. It’s an art style with a lot of play in it, bold about flatness, but working well in the game’s 3D, first-person environments, able to keep things readable as you go for long hikes and retrace your steps, while also conjuring everything from stone forts to discarded oil drums. And as things get darker and more oppressive, the colours shift and become more fretful, the skies and shadows looming. Your job changes from one chapter to the next, but it generally entails capturing footage of the local squirrels on video. To do this you have to work out where the squirrels are at the start of the day - happily, in-game squirrels are happy to retrace their steps identically every day, and maybe real squirrels do this anyway? - and set up a camera. Then, over a course of days and nights, you learn about what the squirrels are doing. This is the game. First night, first camera set-up. Do you see a squirrel? Where does it enter and exit the frame? Second day. Based on those entrances and exits, where can you place a camera to capture the next bit of action? And the bit after that? A surprising number of different objectives are available with such a set-up. Where do the squirrels come from? Where is their stash? Can you capture - I hated this one - specific moments of their daily wandering? There is something rather crushing about the job that is revealed by this loop. Each day I wake, move a camera maybe a few feet and then return to the camper to trigger the evening shift and a review of the footage, and jeepers, that single camera movement was my entire day! But quickly Nuts builds up the cameras until you have three, and then there’s a bit of fun to be had exploring the game’s small but evocative levels. Sometimes I tried to predict where the squirrel’s stash would be, long before my daisy-chaining of camera viewpoints had revealed it. I was always wrong. And there’s also the developing plot to keep an eye on, revealed in faxes and phone calls from your boss as you submit squirrel photos and complete tasks, but also hinted at by the movements and noctivagant congregations of the squirrels themselves. I had a friend once who admitted he couldn’t watch The Muppet Show as a kid, when he realised that the theatre audience for the Muppet Show were also muppets.. I get a little of that shudder in Nuts, when I realised that I am living around these squirrels, and that I have my agenda and that they have their own agendas, and really if I’m absolutely honest, I’m following and they’re leading. Things speed up towards the end of the short narrative, but this is the crux of it: you will like the main gameplay loop or you will hate it. I loved it. Where others may correctly see busywork and backtracking and annoying failures, I started to relish the incremental acquisition of new knowledge, the instance of the fingerpost when everything comes together. In retrospect, I think Nuts is a game specifically tailored for the plodders, but also the catastrophists. It’s for people who shuffle through life methodically, but have minds forever spiralling outwards with plans of possible chaos and misfortune. People who watch squirrels and are maybe a little jealous of their obvious agency, of the glittering clarity of the world in which squirrels seem to operate. Nuts, at times, is a real trip.