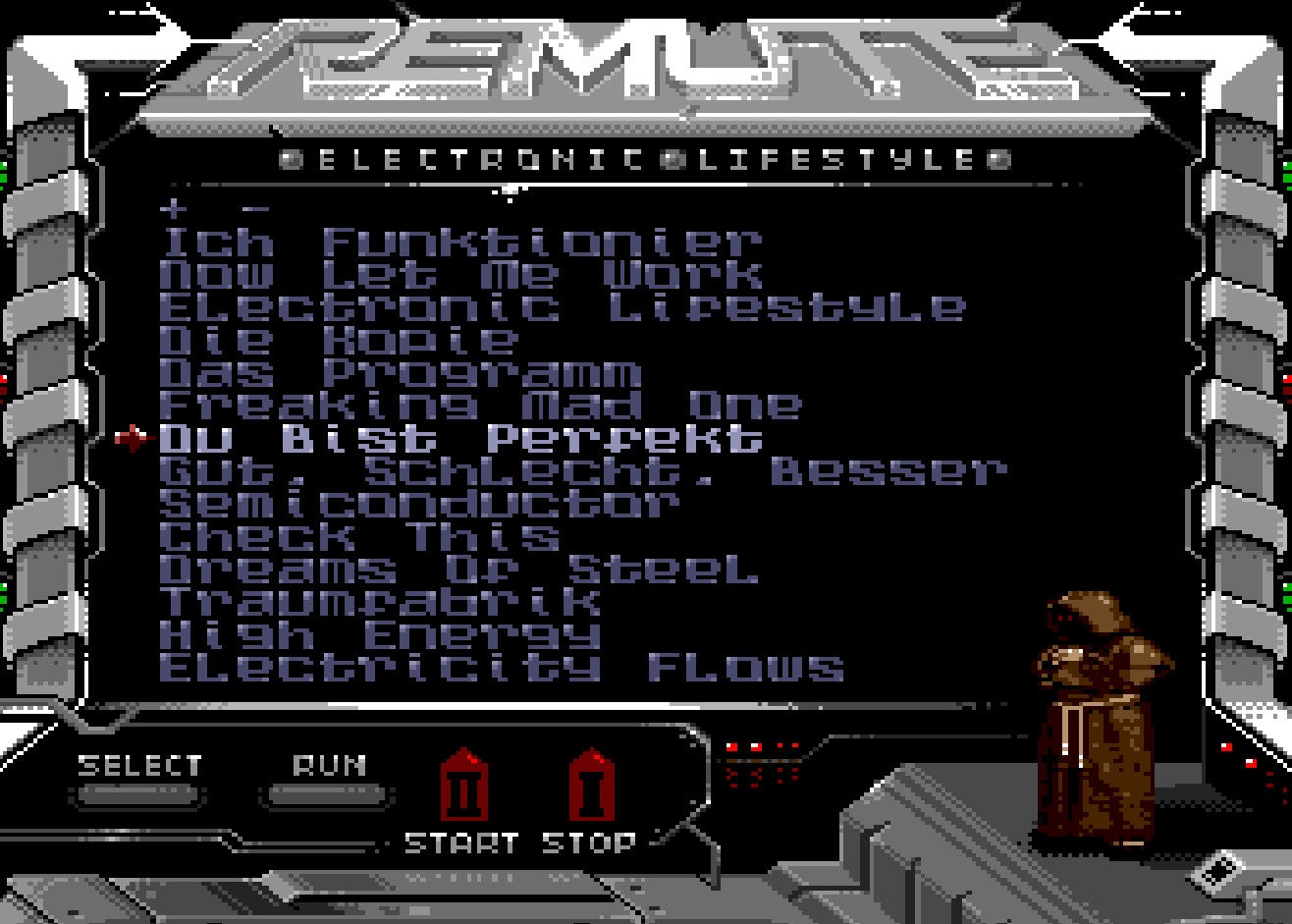

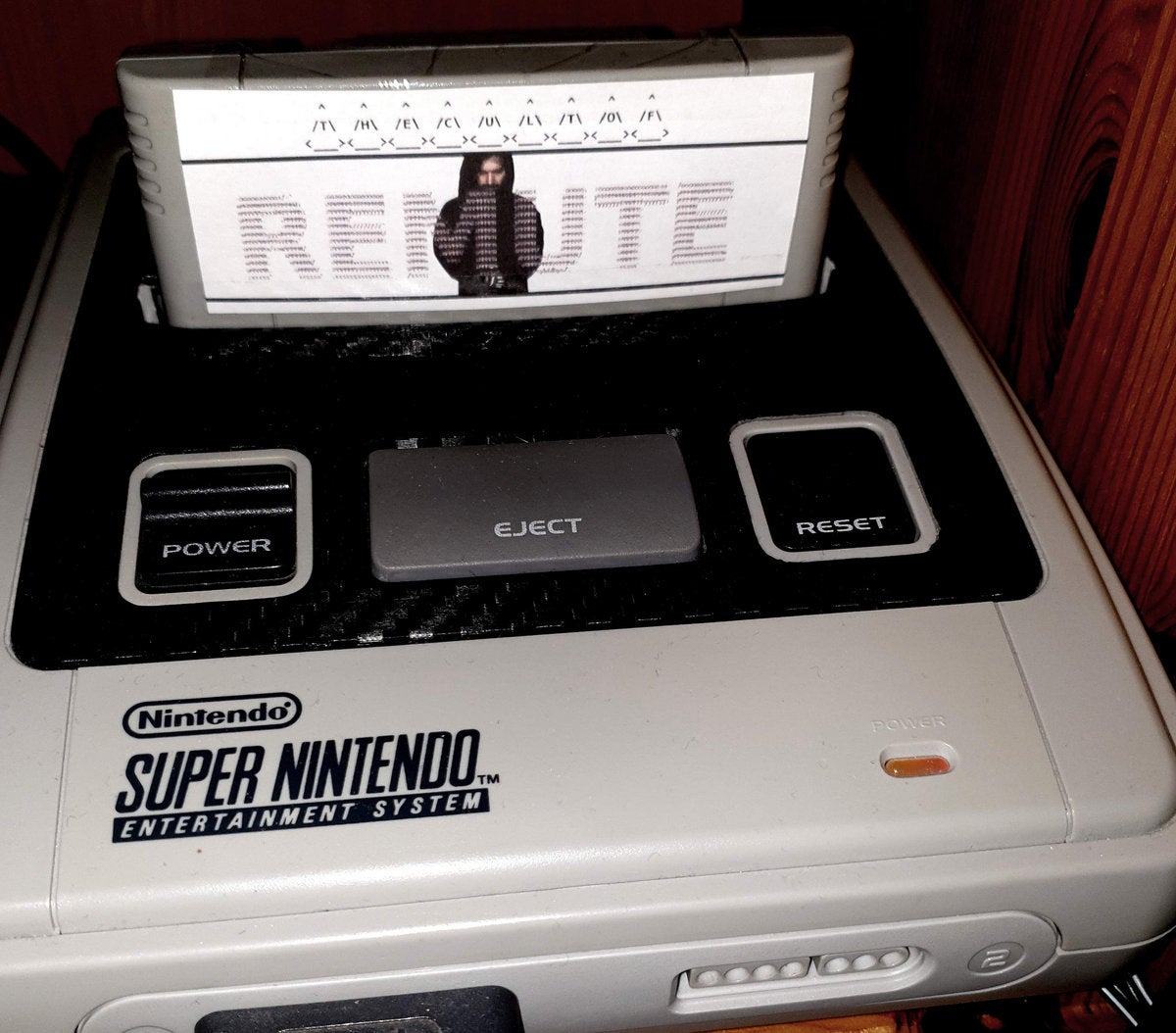

Video game music is big business. Chances are if there’s a game you’re eagerly anticipating, the release of its original soundtrack isn’t close behind, whether it’s conveniently on Spotify or pristinely packaged as a vinyl record from iam8bit or dozens of other specialists that have emerged in the recent years. Yet for Remute, that’s all a bit too safe and conventional. At least for a producer who specialises in electronic music. “I think the most uncreative moment is recording music on a medium like vinyl or CD,” he tells me over Zoom. “It’s good for rock or classical music, but when you record electronic music on it, then it’s a dead medium - it’s just playback.” Based in Hamburg, Germany, the techno DJ and producer is a veteran in the underground electronic music scene, and since his 2006 self-titled debut he’s put out albums on contemporary techno labels like Tresor and Tron. But by 2017, he had become bored. “Everything [about the business] was so normal, and I don’t like normal and safe stuff,” he explains. “I needed to find a way to present electronic music in a more authentic way, so I thought, why not present electronic music in a medium that’s more fitting to the nature of electronic music?” Ironically, his new direction forward would take inspiration from the past. As a fan of video games since the age of five beginning with the Commodore 64 - he cites the hardware’s SID chip as his introduction to electronic sound, notably fellow countryman Chris Huelsbeck’s iconic Turrican soundtrack - Remute’s work has undoubtedly had a lot of influence from video games. Indeed, part of his career had included licensing his music to video games or even composing for games, including interactive fiction smartphone game Somewhere, as well as a number of other games that never saw the light of day. Some of this was then repackaged as an album aptly titled, Theme Tunes For 10 Games Never Made. But it’s specifically the consoles and computers from the 16-bit era and before that fascinated him the most. We might think of chiptune mostly as a genre or aesthetic choice, but they literally did come from the sound chip, using code to generate music in real-time. It’s this “living electronic sound” that essentially led to Remute’s decision to release albums specifically for games consoles. Technically, his experimentation in alternative audio formats began with the Amiga, when he released his album Limited on both vinyl and floppy disk. However, for his first full console album, there was no candidate more perfect than the Mega Drive. “Mega Drive was always my favourite sound aesthetic because of the FM synthesiser,” he explains. “Streets of Rage 2 was also my favourite game soundtrack ever, so I thought, when I do an album for a game console, it has to be the Mega Drive first.” Of course, there’s already a fair share of hobbyists and retro musicians emulating the sound of classic consoles using making music that emulates the Mega Drive. Open-source music trackers like FamiTracker or Deflemask were both used to create the 8-bit and 16-bit soundtracks of indie ninja Metroidvania The Messenger. According to Remute, who used the latter to write the music for his Mega Drive album, Technoptimistic, it was initially a difficult learning curve. “On the other hand, it felt really fresh and it was the kind of creative rebirth I needed.” Not content with simply converting the results to an MP3, CD or other conventional music format, he was adamant about making this a genuine Mega Drive album - that is, translating that code onto PCB then packaging it into a cartridge that can actually play on a Mega Drive console. That’s perhaps the most daunting aspect, since this isn’t possible to do in an industrial manner like pressing vinyl or CD. “Things have to be done manually - you have to order chips, you have to order cases. In the end it’s a lot of manual work, but on the other hand it’s pretty fun for me because I like to build stuff!” While he didn’t give a precise number of how many of these limited cartridge albums he made, he laughs and says that it was “a lot” but also adds that every single one was sold. A bonus to playing an album play on your TV also meant that a music video could be included in the cartridge, giving the package a full audiovisual experience typical of the demoscene, a subculture of programmers, artists and musicians who get together for LAN parties to create audiovisual demos from old hardware. For this, Remute enlisted demosceners Kabuto and Exocet, the former a core part of the demoscene group Titan, acclaimed for their jaw-dropping Overdrive demo (you should seriously give it a watch) that stretched the Mega Drive’s technical capabilities way beyond anything else. You can see this in the way Technoptimistic’s ‘Red Eye’ video utilises live-action and pseudo-3D effects that can run on any Mega Drive console without an extra chip, a la Virtua Racing. Technoptimistic was just the beginning though, as last year, he released another cartridge album, The Cult of Remute, but made for the SNES, perhaps an unusual choice as its audio quality isn’t usually talked about in the retro music scene. According to Remute, however, writing music for Nintendo’s 16-bit console was actually very similar to his work on Amiga. “The greatest obstacle was compressing sounds and shrinking them down so that they still sound like something,” he explains. “They sound pretty muffled and lo-fi, but on the other hand, the SNES has some very special post-processing effects that makes the sound more lively again.” The SNES also differed from the Mega Drive as it didn’t have a sound chip so much as a whole audio subsystem that played digital samples aiming for a more realistic sound, such as Super Star Wars’ accurate albeit tinny rendition of John Williams’ classic score. “Soundtracks like Zelda or Final Fantasy had so many orchestral elements, which sounded completely fake and artificial, but somehow I also liked this pseudo-realistic sound,” says Remute. A contrast to the “cold, sci-fi, robotic” sound of the Mega Drive, he wanted The Cult of Remute to have more of a sample-based sound that reflected the SNES’s qualities. “I used many samples that I’ve used before and converted them down to a format the SNES can read. It’s kind of a ‘Best of Remute’ album, but all the songs are also new!” It then only seemed inevitable that his forthcoming release Electronic Lifestyle would be for the PC Engine. It’s proven to be the most challenging console album, largely because of both the console’s rarity and its unique HuCard format (“What kind of magic is this, to fit stuff on a credit card-like size?”) Nonetheless, Remute explains he always had it in his mind to make a PC Engine album, despite only being able to get hold of one himself in recent years. “This was always the console I couldn’t afford as a child because in Germany it was import-only and super-expensive. But I would watch this console in shops and it always fascinated me because of the high quality game library. I also really liked the sound because I always thought it was a mixture between NES, Amiga and Game Boy - it’s probably an NES on steroids, because it has a very harsh but unique digital sound.” Once again, he had coding help from another Overdrive alumni, pixel artist Alien, as well as MooZ, a programmer experienced with making his own PC Engine demos who was able to translate the music programmed on Deflemask to run on PC Engine. As for the HuCards, these had to be custom-made by a PCB engineer from Sweden called Mr Tentacle. However, due to the difference of HuCard pins, he’s had to limit the numbers made for the TurboGrafx-16 version by pre-order only, which has closed at the time of writing. Yet for such a complex undertaking, if making albums for the Mega Drive and SNES sounded like a niche market already, it must be even more so for a console so rare and expensive. Considering that these albums will still be available via digital and streaming platforms, isn’t the business of making them for the host hardware too costly and foolhardy an endeavour? “The businessman in me probably says, ‘Remute, are you crazy?’,” he laughs. “The artist in me says I have to do it for the PC Engine! Fortunately, the artist in me was always stronger than the businessman.” He also happens to have the good fortune that at around the time he announced this album, Analogue had also revealed it was making the Analogue Duo, which can play PC Engine, TurboGrafx-16, SuperGrafx and PC Engine CD-ROM² games. Considering Remute owns the Mega Sg, which also happened to release in the same month as his Technoptimistic cartridge album, they seem likely partners. “We don’t have a connection, but I like what [Analogue] are doing because they have a really good quality, which is perfect for modern setups. It’s just brilliant timing and I think they really fit well together.” But could the PC Engine also be the last of his console albums? After all, by the time we move into the 32-bit era, sound chips were left behind in favour of CD and digital audio. While many would argue that the PS1 was a musical revolution for games, Remute is less enthused. “I really miss today’s consoles having a unique sound,” he laments. “I always find it very fascinating that these old consoles all have such unique sound capabilities that you can hear that this is NES, this is Mega Drive, this is Game Boy, this is Amiga, and so they have a lot of character.” Because of the unique qualities of the sound chip, from the C64’s SID chip to the Mega Drive’s Yamaha YM2612 FM Synthesiser, each system can almost be treated like a musical instrument with its own distinct sound. As a simple example, you need only compare Yoko Shimomura’s Street Fighter 2 title theme on the SNES, Mega Drive, Amiga and CPS1 arcade board. Whether he might continue the cycle and release another Mega Drive album or perhaps go back to his first love the C64, Remute is currently tight-lipped on future plans, though he hints that it will involve game soundtracks. “What I probably learned from the old-school platforms was that their game soundtracks are very dynamic and react to the players,” he says. “So when doing modern soundtracks for modern platforms, I always have this old school sound aesthetic in mind.”