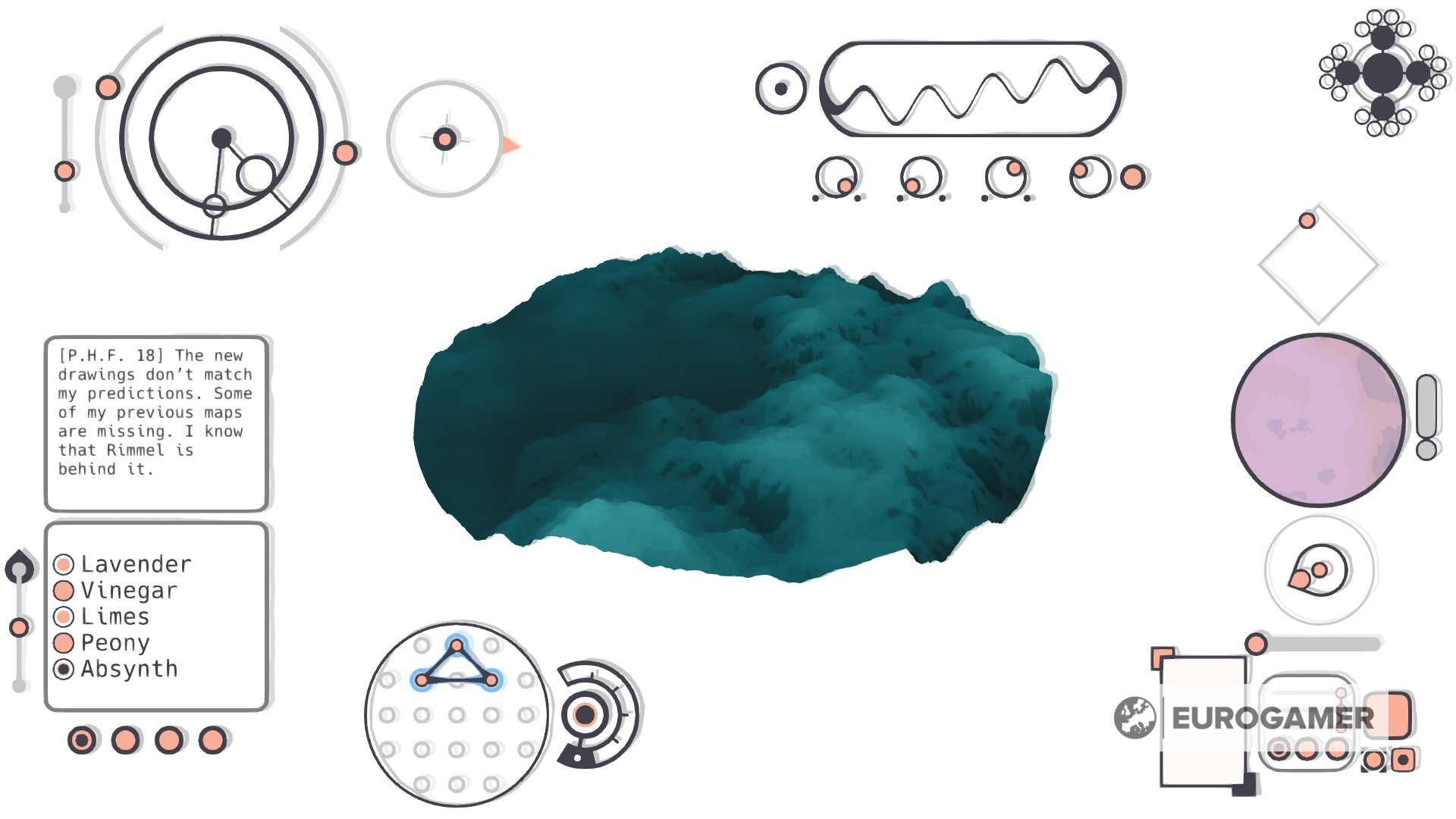

Mu Cartographer is like looking down on an alien world. It’s one of my favourite things in all of games, an activity bear - a screen filled with buttons and mechanisms and you have to find out what each one does. The chat box! The peg board! The twisty thing. The…actually what is that? This is the game, but the game is also projecting yourself into the fiction, because at the centre of your attention is that shifting mass of colour and volume. Is it a weather radar? A landscape? Are we inside a body or under the ocean? None of this should be spoiled. Just enjoy it. I tell myself that anyway. Prod and twist and dial and move things around on the peg board, but I always end up trying to pull everything together. The promise of exploration, of a perfectly bizarre mystery to solve, is just too powerful. I cannot resist it. And so I make notes, I create theories. I give tentative names to the objects and try to piece the fragments of story together into some sort of narrative that makes sense. I scan the surroundings - if they are surroundings - and I feel a certain desperation that I am missing something, or passing up an opportunity to understand something, that I have already failed. That’s the final bit. I spread the message. Maybe you can play Mu Cartographer and maybe you can tell your friends and they will tell their friends and one day I will be enlightened. What a fabulous, terrorising thing this is. Bertie: Games like this have a wonderful power to draw you in, because by not giving you very much, visually or otherwise, they leave your mind with an unanswered question. And you know what an unanswered question feels like in your head, don’t you? So your mind reaches. It clings onto anything it finds. Mu Cartographer revels in this. You don’t know anything to begin with. You don’t know where you are, how anything works, or what you’re supposed to be doing. So like a baby in front of a plastic sensory toy, you fiddle, you prod, you poke, and gradually - and I do mean gradually - some things begin to become clear. Then, into this hungry state of mind, the game drips story. Fragments of an exploration emerge, written by the people involved. Who they are and where they are, again, you have no idea. But judging by the machinery around you, and the images you’re seeing and accounts you’re reading, they’re probably somewhere very far off. This scarcity of information lays the groundwork for piercing moments of clarity, because Mu lulls you into a mindset where you’re used to everything being obscured. Most of the time, the world is an abstract topographical image, something that requires interpretation, something hard to make sense of. But occasionally, it comes into focus. Using a kind of frequency dial, you can tune into the world like you’re tuning into a radio station, and when you find the right signal, things are suddenly there. Actual, discernible things, defined shapes, even places. You’re suddenly seeing what the explorers saw. It’s powerful, and I think these moments are the real treasures in the game. It reminds me so much of a game released last year, called In Other Waters. That’s another game that takes you somewhere else, and has you interact with the world a step removed, through a machine’s interface. It’s also another game that gently, calmly, reveals a story about the world you’re in. They’re both peaceful and very pleasant places to be.