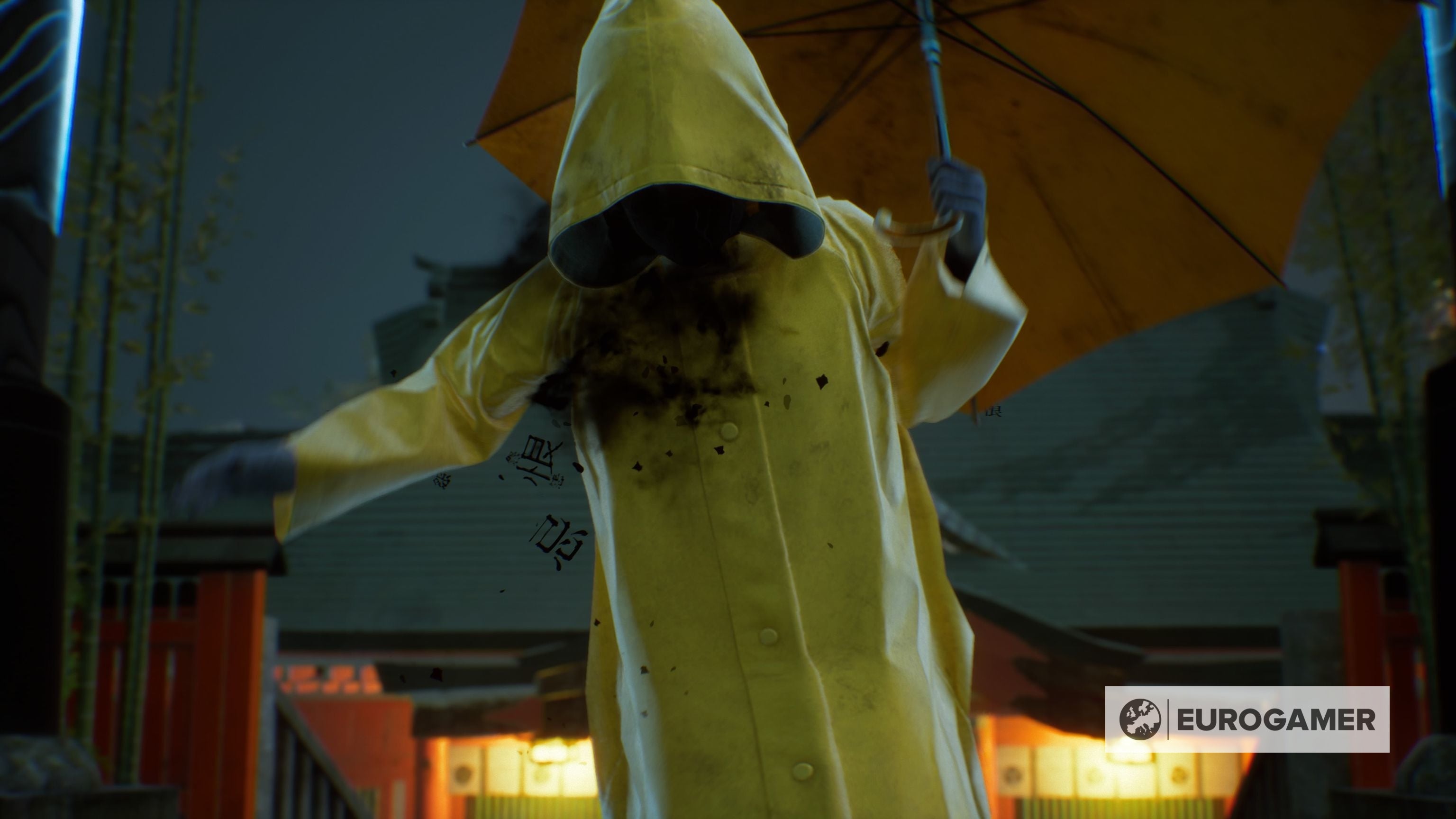

For all the sights and sounds of Ghostwire: Tokyo - and trust me, there’s a lot of ’em - it’s these sets of clothes that touched me most. Despite a mainline story that does its utmost best to pull at your heartstrings and connect you in some way - any way - to Akito and his psychic roommate, for all its cloying sentiment, nothing in that story made me feel as sad as the sight of all those empty outfits. It’s to my considerable frustration, then, that Tango Gameworks kicks off Ghostwire: Tokyo with such a dazzling conceit but goes on to do so very little with it. Much like the neon and the puddles, the pray sites and the Jizo statues, most of what you encounter on the empty streets of Shibuya are just props. Window dressing. Though occasionally you’ll find a note or a phone or some small keepsake to identify the hospital scrubs or the business suit or the school uniform beside them, most of the time you won’t. Most of the time, the people of Shibuya don’t seem to matter. I suspect that’s why I enjoyed Ghostwire’s side missions so much. Though a touch uneven, and often recycling the same handful of core mechanics - go here, kill this, grab that, come back - it was gratifying to at least put a story if not a name to that particular pile of clothing on the street. Those missions - along with the endless but wholly gratifying pursuit to feed the city’s entire population of abandoned cats and dogs - were a delight. That’s not to say I didn’t enjoy Ghostwire’s truly dizzying blend of urban monotony and supernatural spooks, though, because I very much did, and it’s a testament to developer Tango Gameworks that in spite of my disappointment with some aspects of its storytelling and core gameplay, I was suitably invested right up until the very end. I don’t know how much of the story you know (and if you hope to go in without prior knowledge, as I did, I’ll do my best here to hold back) but suffice to say you play as Akito, an everyday dude thrust into an entirely un-everyday life, fighting to free the city and a loved one from the tyrannical clutches of a rogue occultist. And the day the city’s inhabitants disappeared was the day he found himself invaded by a spectral hitchhiker, KK, through whom Akito can imbibe otherworldly powers. I know, right? It’s an utterly outlandish, outrageous story that is never concluded in any satisfactory way, and yet it’s so utterly at peace with itself - so unapologetically over the top and in your face - that you find yourself wanting to play on, anyway. Sure, there are gaping plotholes and it exaggerates everything it can at every single opportunity, but these juxtapositions - the real-life drudgery and the fantastical; the car alarms and the supernatural screeches; modernity against mysticism - only add to its charm. The problem? It’s the combat. It’s not that it’s bad per se, but it’s not particularly good, either, straddling a no-man’s-land of mediocrity where sometimes it feels perfunctory, and other times just frustrating. When you take on the many guises of your enemies, colloquially known as Visitors, you fight not with bullets but with magic, harnessing the elemental powers of wind, water, and fire. The latter, Wind, is your quick-fire, everyday weapon, whilst you’ll pull out your restricted reserves of water and flame magic to tackle the big ‘uns. And it looks spectacular, by the way. Akito’s fingers fly fluidly to snap emerald tornados or red-hot fireballs at nearby foes, but that’s pretty much the only thing that feels fluid about Ghostwire’s combat. Your enemies flail about widely and Akito’s blessed with the reaction prowess of an arthritic tortoise. I accept you might be better than me, but I suspect you’ll also miss more shots than you land, too, and even utilising the game’s lacklustre aim-assist doesn’t do enough to ameliorate the issue. Combat does get better the more you play, but it never gets good, I’m afraid. Out and about in Shibuya this isn’t too troubling, but in boss fights it can be lip-bitingly annoying, as your fingers are powered by Ether and - for reasons I don’t understand, either - random items shimmer with the sheen of a supernatural oil slick that, when struck, explode into Ether shards. Consequently, street fighting rarely gets problematic as there’s usually something you can smash nearby, but boss fights - again, fine, if unremarkable - definitely can be made unnecessarily scrappy difficult because of this. Sure, you can use talismans to help tip the balance in your favour, but as even the weapon-select wheel is floaty and sluggish to use, I learned not to rely on those in times of pressure, either. There are also a couple of instances where KK is forcefully severed from Akito, and these are, without doubt, the most tedious sequences of the game. The one non-magical tool in our arsenal is a bow, although, for all the good it does, you might as well bin it and just throw arrows at enemies. I found stealth kill “purges” and good old-fashioned running away did just as good a job the few times the game let me do so. The Visitors themselves, though? They’re gloriously horrifying and horrifyingly glorious. Plucked directly from Japanese folklore, horror stories, and the nightmares of children, you’ll take on a Slender Man clone with no eyes; cartwheeling, and headless, schoolgirls; a young man with martial art expertise; and a hideous woman who blows deadly kisses at you that, given Akito can’t roll, I could rarely avoid. Later, you’ll take on the slit-mouthed scissor woman - or Kuchisake-onna - and though her variant will pop up several times before Akito completes his adventure, I’m still absolutely terrified of her. Despite their different attack methods, though, yours rarely deviates from what you learn in the opening five minutes of the game. Shoot-shoot-shoot, wait for their “core” to be exposed - hearts, essentially - and then lasso them with a magical whip. If you’re lucky and uninterrupted, you’ll get to dispatch them there and then. If you’re not, round two will ensue until one of you is dead. Them, usually. There’s more, of course: a lot, more, actually. I suspect some may tire of the game’s endless demands to find, and then cleanse, Torii gates - a cyclical task to clear the evil fog that clouds the streets and gates your progress - and every time I stumbled across an infrequent site of corruption - a pinky-black goo that grows in tendrils and blocks your path - I had to remind myself what it was. One of the game’s most novel mechanics, hand seals, became so tedious (and occasionally unresponsive) I stopped doing them, gratefully giving in to the “Leave it to KK” button that Tango put there, presumably because it too figured we’d get sick of it. Most of this is aided by Spectral Vision, a blue filter that descends over Akito’s sight to let him better see access points, ladders, Ether, Tengu - terrifying bird things that screech overhead but, for reasons I don’t understand, kindly let us grapple off their claws - and, perhaps predictably enough, it’s so useful that you’ll often be obscuring Tokyo’s stunning neon-soaked sights with that dreary filter. To expedite levelling up, you can wander around Shibuya hoovering up the lost souls of the city with a paper katashiro, which you can liberate courtesy of a highly-complex spirit transmission service operating from public payphones. You’ll never run out of health items. You’ll never run out of Meika, the city’s currency. The skill tree is unremarkable. On the plus side, cats now run the city’s stalls and shops - if a canine made the cut, I never met them - and oh, did I mention that your magic motorbike runs on fragrant underworld oil? But just when you’re about to give up, Tango throws in some deliciously unsettling sequences that remind you why you’re here. A delectable stew of modern horror tropes - think Bloober games, good old PT and yes, even The Evil Within, with warping worlds and spooky shenanigans - they’re made to scare and unsettle you, and scare and unsettle is exactly what they do. Each one of these vignettes was a rare and welcomed - if all too brief - treat. If you’re looking for a supernatural game that satisfactorily answers all your metaphysical queries, Ghostwire: Tokyo is not the one, I’m afraid. But while it frustrates me that Tango didn’t make the most of its wonderful conceit, I can say that - dull combat aside - exploring Shibuya never bores. With one foot in the present and one very much mired in its Folklore-y past, Ghostwire: Tokyo feels simultaneously both faded and fresh. And if nothing else, I’ve learned few things warm my heart as much as a lonely Shibuyian pooch telepathically saying “Thanks! You’re nice!” when I share a handful of dog food.