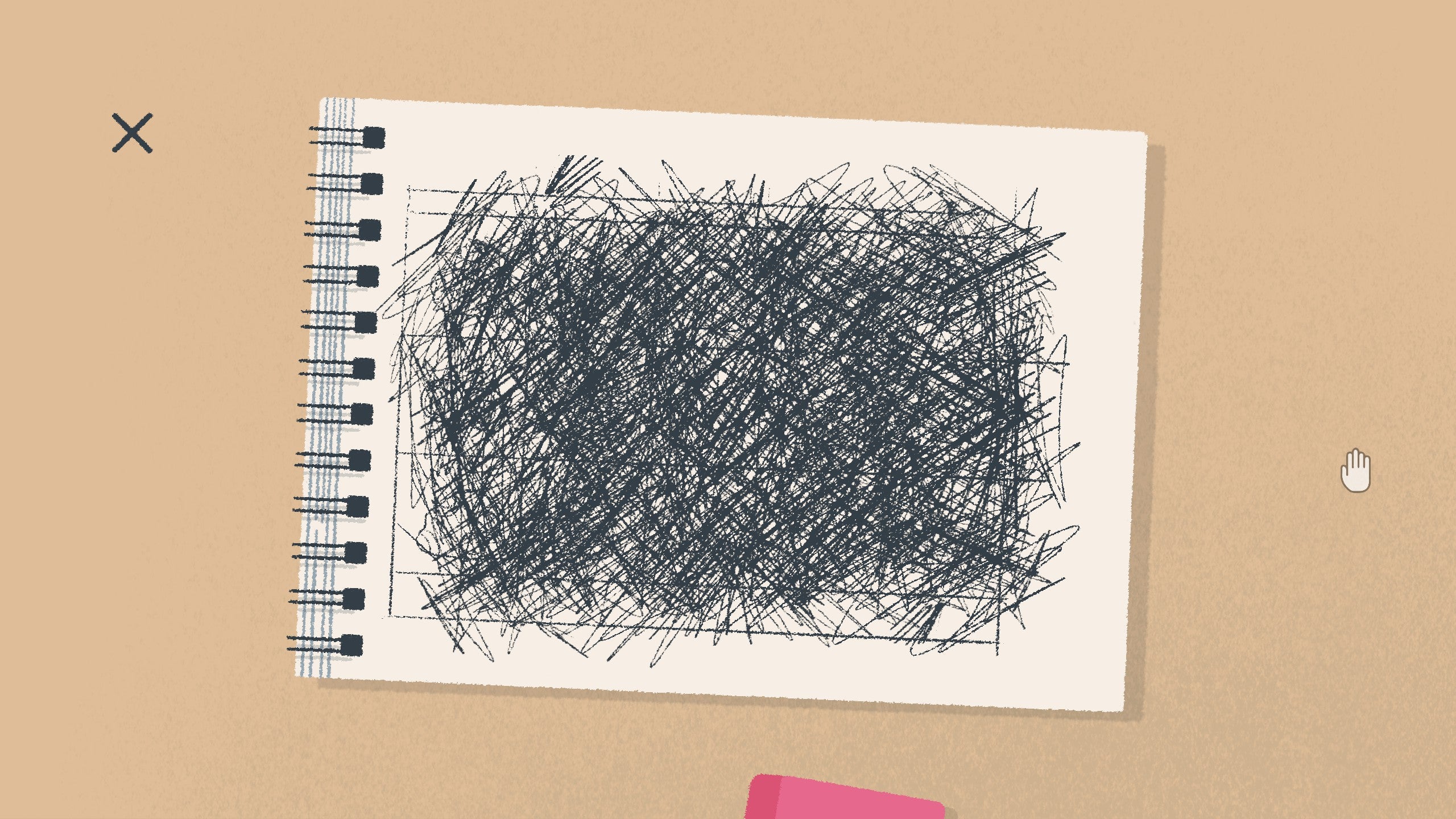

Let me explain. Imagine there’s a random set of books in front of us. You might choose to order them in alphabetical order by author. I could choose to order them by title instead. I could go for something less practical like the colour of the covers, which wouldn’t be of much help if I needed to find a particular book, but it’d be aesthetically pleasing. Part of the power of organising comes from creativity and control. There is no “correct” answer in tidying, but A Little to the Left asks you to find it. At its worst, I felt like I was on the world’s most frustrating episode of Only Connect, without a Victoria Coren-Mitchell to debate my answers with. And this is where A Little To The Left struggles where others, such as Unpacking, succeed. I can choose how to categorise things, and someone else might see a different way to categorise them but they’d both be equally as valid. There’s creativity to tidying, but as soon as you frame it as a puzzle to be solved it’s no longer an exercise for your own mind. Some puzzles in A Little To The Left do have multiple solutions, but too often I found myself asking “how do you want me to arrange these items?” rather than “how do I want to arrange these items?”. Sometimes, I found myself so stumped on how to place everything, despite understanding the general pattern of what the game wanted me to do, that it all felt terribly annoying. Some solutions aren’t all that intuitive, and I only managed to solve them thanks to trial and error. These puzzles are usually the ones which will “snap” an object into place if you’ve put it down correctly, but there’s little satisfaction to be found by using brute force. In the ones which don’t have this “snap”, you may have things placed correctly, but just slightly off from the position it needs to be in for the game to register it as solved. Luckily, Max Inferno added a feature called “Let it be” based on feedback. It allows you to skip a puzzle and move on to the next, so you can continue progressing even if you do get stuck. It’s a welcome addition for when a puzzle just isn’t clicking with you. There’s also a hint system which consists of a hand-drawn sketch of the answer, leaving you to just arrange everything on the screen so it matches the sketch. I disliked this because a hint should never give away the answer immediately. In the end the hint almost serves the same purpose as the “Let it be” feature, allowing you to move on to the next puzzle whilst also removing the fun of figuring out the answer. If this was purely a game about tidying things up, being given a blueprint to follow wouldn’t be as disappointing. But it is, and it’s a shame that the subject A Little to the Left uses to present its puzzles is organising, because despite those few (slightly infuriating) frustrations I mentioned before, it’s actually a really good puzzler at its core. Most of them are well-designed and require a range of logic. Some of them rely on you recognising a pattern, or making sure you’ve been paying attention to the themes of previous solutions. There’s also Max Inferno’s own unique takes on classic puzzles. One standout involves jigsaw pieces, but the aim isn’t to fit them together to form a solid rectangular picture. Another puzzle is like a tangram, but with extra rules that help you to figure out where to place each shape. There’s even a couple of variations on Tower of Hanoi (or what I always remember as the pancake stacks in Professor Layton), in which you need to stack objects in size order. These puzzles, which are often the ones with only one solution, are the most satisfying because there’s a common understanding they’re built on. I know what you want me to do when I’m given jigsaw pieces. I don’t know what you want me to do when I’m given a bunch of different leaf shapes. When the game gives you puzzles which easily click or can be deduced with relative ease, it’s a delight to play. You’re learning more about the developer’s way of thinking than might be obvious at first glance. It’s as if you’re truly getting a look into how they would arrange their home. This is even emphasised by the game’s visuals and tone. Objects will rattle and shake as you interact with them, each with their own unique sound. The thump of a cardboard box, the crunch of a slice of toast, and the squeak of a cloth all exist to remind you of the game’s domestic setting. It was difficult for me to ever be truly annoyed at the game when the depiction of each object has been so carefully created. The game favours a cool-toned pastel palette which keeps it easy on the eye, and the soundtrack uses lighter instrumentation such as a xylophone and a range of string instruments to maintain a bright and breezy atmosphere throughout. It’s a shame, then, that A Little to the Left is held back by its nature as a puzzle game. Despite its beautifully hand-drawn graphics and mostly well-thought-out puzzle design, it can’t escape from the contradictions it introduces by giving hard solutions to the freeform creativity of tidying up.